No Chance Of Survival: How A Deadly Plane Crash Yielded A Growing Spiritual Harvest

Two years ago, a plane went down near Yoakum, Texas. That was odd—planes don’t often crash, especially when, like this one, they’re well maintained with an experienced pilot.

Even more unusual was the collection of men on board. The pilot was a church elder. In the seats around him were a lead pastor, an executive pastor, and two serious Christians. All of them belonged to Harvest Church in Germantown, Tennessee.

That was enough to grab news headlines. But it wasn’t even the strangest part of the story.

The plane, a six-seat Piper Malibu Mirage, hit the ground with a G-force of 90, which means the pressure at impact was 90 times the force of earth’s gravity. It was so fast that the plane’s wings were severed, its nose demolished, and its cockpit roof blown off. For most of the men, death was instantaneous. Later, an insurance company expert determined the odds of survival were zero percent.

And yet, somebody did.

“A couple things hit me in waves—the shock of just a moment ago, [the pilot] was saying, ‘Hey, we’re gonna land, here’s what we’re doing,’ and all of a sudden, we crashed,” Kennon Vaughan said. “And with that shock, the shock that I was still alive, it hit me in an instant—this is a miracle.”

Kennon is a graduate of two seminaries, the founder of Downline Ministries, and the planting pastor of Harvest Church. He’s a son, a husband, and the father of five boys.

And for some reason, he’s alive.

“I don’t think it was any fluke or any luck: ‘Man, your body was at the perfect angle,’” he said. “I think God’s hand kept me alive because of a divine purpose [and] that the gospel will go forth through this in a unique way that I believe God’s sovereign over. I think that’s the only reason I’m here.”

It already is. In the aftermath of this crash, many people have come to know the Lord. And it isn’t a stretch to say this harvest is just beginning to come in.

Kennon Vaughan

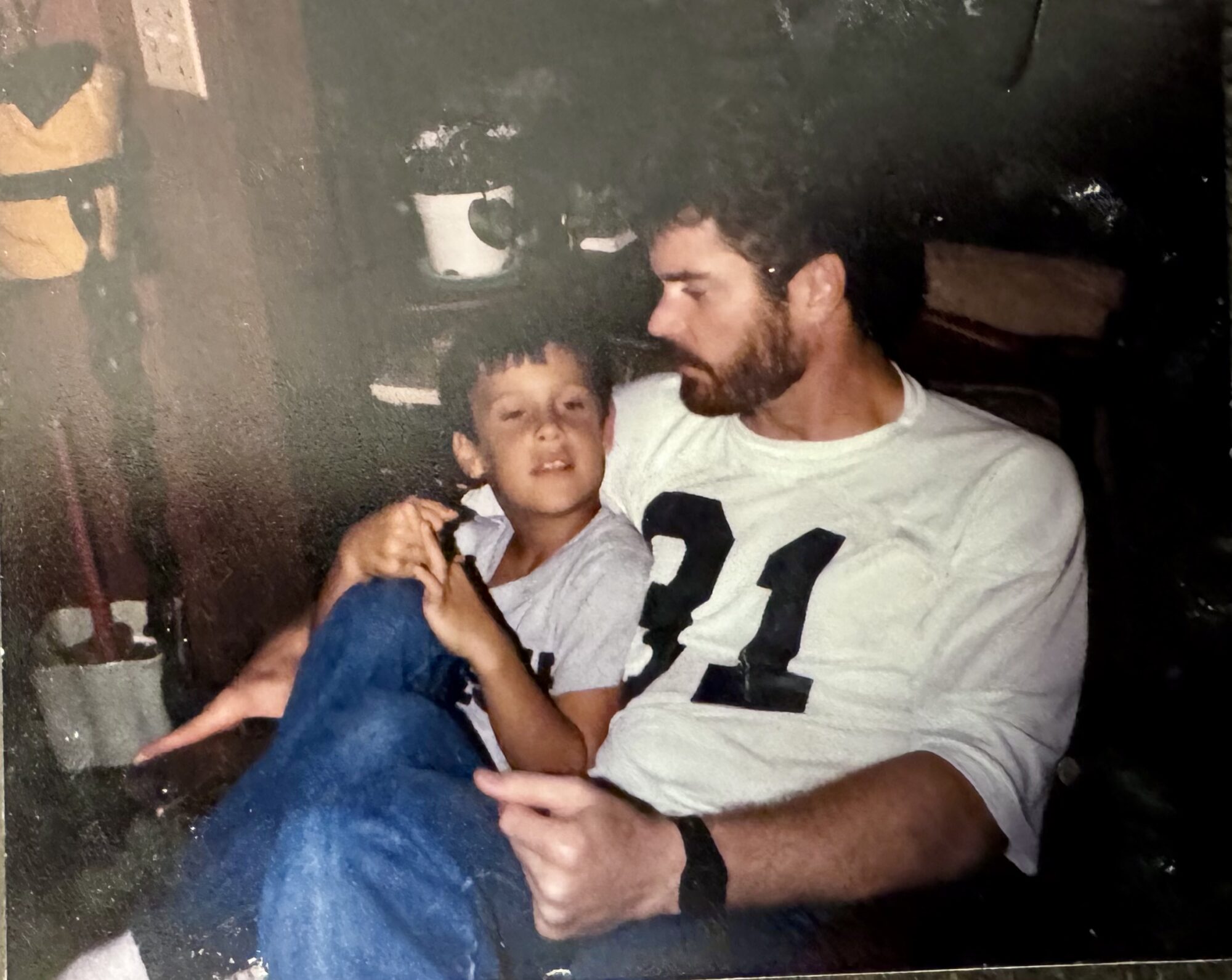

Kennon was born and raised in Memphis, where tragedy came early: When he was 16, his father sat the family down to tell them he had brain cancer.

Kennon was a young Christian, and he prayed constantly for the Lord to save his dad. God didn’t—the doctors estimated Kennon’s dad had three months to live, and they were right. But God also did—just weeks before Kennon’s dad passed away, he reconnected with his faith and truly surrendered his life to Christ.

Kennon and his dad / Courtesy of Kathryn VaughanWithout his dad around, Kennon made his way through Auburn University, wondering if he should be a teacher, or maybe a coach. On an Athletes in Action mission trip to South Africa, he learned how to share the gospel. God moved, and Kennon saw people come to know the Lord. He came home consumed with the desire to tell everyone about Jesus.

After graduation, he took a job as a youth pastor, but quickly realized he didn’t have the depth of knowledge or maturity to minister effectively to the students.

“And here I am every week trying to come up with a message for the kids,” Kennon said. “I just felt overwhelmed, new. I needed somebody to help me understand the Bible for myself, much less [how] to teach it to the students.”

His senior pastor suggested he ask a few older men to help him. The first name on the list was Soup Campbell, a well-known Christian leader who lived in one of the most difficult, impoverished neighborhoods in Memphis.

“And he came,” Kennon said. “He brought a couple of van loads of kids out of his own neighborhood, showed up, taught out of John 15. . . . He walked verse by verse through the first half of John 15. I had never heard anyone teach in that way, exegetically expositing God’s Word. He knew the original language. He had such insights. For the first half of teaching, I was like, How do you know the Bible like that? And then . . . his delight in the Lord was so tangible and authentic, and I started thinking, I just want to know Jesus like that.”

Discipleship Drought

Kennon asked Soup if he could study the Bible with him. He was asking the right guy—Soup was a true disciple-maker.

“When I saw disciple-making, I saw a ministry that would be multiplying,” Soup said. “Done right—if it’s done after the biblical standard of Jesus—it will continue till he comes again.”

Soup and Kennon started studying the Bible together at 5 a.m. every Tuesday.

“He was someone I could follow,” Kennon said. “For the first time in my 10 years of being a Christian, my spiritual life began to really grow. Things were heading north. I wasn’t just kind of bouncing around, struggling, and wishing I knew more, and wanting to learn more, and wondering where I was, and kind of drifting. All of a sudden, there was great intention, just with being able to follow a man more mature in Christ than me.”

Soup Campbell (left) and Kennon (right) with Kennon’s mother, Pege / Courtesy of Soup CampbellKennon loved it. He started dreaming about all his youth group students being discipled by mature believers in the church. Excited, he started asking if anyone would be interested.

“The more I asked men and women in our church—really good men and women, really godly men and women—I kept running into the same two objections,” he said. “They would say first, ‘Hey, what do you mean that you want us to disciple? What does that look like?’

“So I would share with them, ‘Well, here’s what I see in Jesus’s life and ministry. And boy, I’m experiencing this with Soup. It’s the most life-giving thing. You don’t have to be perfect—just be honest and authentic and follow Christ right before them and have an intentional relationship with them and apply Scripture in the context of this life-on-life relationship.’

“And then they would say, ‘Well, OK, I want to do that. I want to love them. But hey, I don’t know the Bible that well either. I’ve never been formally trained.’ I can’t tell you how many folks said that. ‘I’ve never been to seminary. I don’t have any formal theological training.’”

Kennon told Soup what people were saying, and Soup suggested asking other pastors in town how they did discipleship training. Kennon asked a dozen pastors.

Here’s what they told him: “Wow. You know, that’s not something we do real well. Our church is good in certain areas, but I would say we’re weaker here. We don’t have many folks doing with the next generation what Soup’s doing with you, what you’re trying to build. Our people would probably have the same questions that you’re getting. You know, I’d love to hear what you find out.”

Kennon sensed the need to see discipleship rekindled in the local church, but he didn’t know what to do. So he prayed. He got connected with Tommy Nelson’s Young Guns program, which trains young men in the Word from Genesis to Revelation over 9 months. He began to see how the whole story of the Bible fits together, and it came alive. After that, Kennon went to seminary and noticed there were no classes on discipleship. He prayed some more.

Finally, he went back to Memphis in 2006 with a vision for a parachurch ministry that would teach the whole story of the Bible, four hours a week, for nine months. By the end, participants would have the ability and confidence to teach their kids, students, friends, family, neighbors, colleagues—anyone—about the Bible. He called it Downline, and over the past 19 years, more than 5,000 people have enrolled.

The first Downline class in 2006 / Courtesy of Kathryn VaughanHere’s why I’m spending so much time on this part of the story.

The elders at Kennon’s church noticed he loved shepherding his students. They also saw he was level-headed, calm under pressure, and methodical in solving problems. So they asked if he’d want to plant a church, and in 2013, Kennon launched Harvest Church in a suburb of Memphis. For the next 10 years, the congregation grew rapidly. As they did, Kennon and his team focused relentlessly on discipleship. They held Bible studies. They arranged small groups. They modeled one-on-one discipleship. And they sent as many people as possible through the systematic Downline training.

By January 2023, Harvest Church had about 30 staff, 30 elders, and 1,500 members. These weren’t casual, cultural, or Christmas-and-Easter Christians. This was a congregation whose roots were wrapped around expositional preaching, classes that explicitly explained Scripture, and hundreds of small-group Bible studies and one-on-one mentoring relationships.

Texas Connection

A couple of weeks before the crash, elder Steve Tucker asked Kennon if he’d like to ride along on his work trip to Yoakum, Texas.

“Steve Tucker was one of the godliest men I knew,” Kennon said. “He was the very first elder at our church. He was like an elder statesman. He was a patriarch even among our elders. . . . We all looked up to Steve. I wanted to get any time with Steve I could.”

Like Kennon, Steve was all-in on discipleship. For decades, he’d been meeting weekly with men in his home to talk and laugh and pray together.

Steve Tucker / Courtesy of Cathy TuckerSteve and Kennon shared something else in common: Texas.

“My family has a four-generation cattle ranch in Texas,” Kennon said. “It’s my favorite place in the world. I grew up going there in the summers. I just love it there. I almost never get there because it’s a ways away.”

Turns out, Kennon’s family ranch was only 40 minutes from Steve’s saddle company.

Steve “piloted his own plane,” Kennon said. “He flew down to Yoakum every single week for the better part of 15 years. That was his rhythm at work—in Memphis half the week, and there [half the week]. And when we put together that connection, he said, ‘Hey, anytime you want to go down with me for a day trip . . .’”

Kennon did want to, and he’d hopped in with Steve about half a dozen times over the past decade. So here’s something Kennon knew about Steve’s plane: It could fit five passengers.

Planning the Trip

“I had met a guy recently—within the last two months—at the church,” Kennon said. “[Tyler Patterson] was a young guy and had started coming to Harvest. He had been on the college rodeo team at Mississippi State. And he’d said to me, ‘Hey, I’d just love to get some time with you.’ That’s kind of a normal thing young men will say in our church to older men, and I’m starting to move into the older-man phase. But he said, ‘I’d like to get a little bit of time with you, get to know you.’”

Kennon thought of the Texas trip he was planning with Steve.

“Weren’t you a rodeo guy?” he asked Tyler Patterson.

Tyler Patterson / Courtesy of Harvest Church“Yeah,” Tyler told him. He’d been a bull rider.

“I thought this would be too much fun,” Kennon said. “I’d love to get to know him in the context of going to see a ranch in Texas with Steve Tucker. So I asked Steve Tucker, ‘Could we take this young guy, Tyler?’”

Steve said sure.

“Bill Garner was my very best friend,” Kennon said. “He was our executive pastor. On my last three trips to the ranch, when I’d go with Steve, I invited him, and he never could go. He always said, ‘I’m going to go on the next one.’ And so sure enough, he was able to come on this one.”

The group was shaping up, and Kennon asked if it’d be OK to invite one or two more. With Steve’s blessing, he asked Jamie Trussell, then the ministry development and teaching pastor at Harvest, to hop in. He said yes.

“I was in Bill’s office and—typical daily routine—I was in there and we were just ragging on each other, talking lots of trash,” he said. “Then as I was leaving—this was Thursday afternoon at like 5:15, so I was leaving to go home for the day—I remember Bill stopped and he looked at me. . . . He said, ‘Hey, Jamie—me, you, and Kennon probably shouldn’t all get on the same flight.’”

Jamie laughed and told him to quit worrying.

One More and One Less

If you’re counting, that’s one pilot and four passengers. They could fit one more. Kennon spotted him from the pulpit on Sunday.

“There was one more young guy who was in my D group, my discipleship group, years ago—enough to really become part of our family,” Kennon said. “He grew up and became a part of our church community and a great adventurer. He had not gotten married and was one of those guys that always had an itch to go traveling. He had just been hiking some trails in Asia and I didn’t realize he was back.”

Tyler Springer was sitting in the front row on the Sunday before the trip.

“That got my spirit excited,” Kennon said. “After church, I was talking to him a little bit, and he said, ‘I have to go over to Dallas on Tuesday because I’m about to have a nephew born.’ He said he did not have a plane ticket yet. I thought, I wonder if you could go with us? Because oftentimes we would stop for gas right there.

“So I ran that past Steve, who knew this young man, and Steve said, ‘Oh yeah, that would be a lot of fun.’ We always loved having Tyler around. So we had a full crew.”

Tyler Springer on a mission trip to Ethiopia / Courtesy of Lindsay Springer RoseIt was meant to be a day trip. The guys would spend half the day at Steve’s saddle company and the other half at Kennon’s family’s ranch. On the way home, they’d stop in Dallas for gas and drop Tyler Springer—the globe-trotter—off to meet his new nephew.

“Monday was Martin Luther King Day,” Jamie said. “The offices were closed, but we had a huge conference we were going to host for Downline. Russell Moore was coming in, and Sean McDowell, and several others. So we were trying to get some last-minute details together. And I was meeting with Kennon about that.”

At the meeting, Jamie realized how much work still needed to be done.

“I remember Monday afternoon, looking at Kennon and saying, ‘Hey, man, I can’t possibly go with y’all tomorrow. There’s just too much for me to do here,’” Jamie said. “In that moment, Monday afternoon before Tuesday morning, I made the decision to stay behind.”

The Flight

At 7:00 on Tuesday morning, January 17, 2023, five guys arrived at the airport—Steve Tucker the elder and pilot, Tyler Patterson the young father who loved cattle ranching, Bill Garner the executive pastor, Tyler Springer the free spirit, and Kennon. Steve packed their bags into the back, showed them how the doors worked, and told them where the seatbelts were. Then they climbed in.

There was no reason to worry, and nobody did. Over 20 years of flying, Steve had logged more than 3,000 flight hours. He knew this route well. He’d owned this plane for three years. Not only was he meticulous about maintenance, but he’d also upgraded both the engine and the control panels. Tyler Patterson, who climbed into the copilot seat, was also an experienced pilot.

At 7:48 a.m., they took off.

Bill Garner (left) and Kennon / Courtesy of Kathryn Vaughan“The fellowship was rich,” Kennon said. “I sat in the back of the plane with Bill and Tyler Springer, who had been on the trip. He was telling us all about his travels. We had a great conversation that I’ll never forget. And Bill, in typical Bill fashion, was speaking into Tyler’s life in some good ways about being intentional and missional and helping him see that that’s where his joy came from versus worldly endeavors apart from the gospel. We were just talking through that and connecting some dots, and two hours passed really quickly. And then we were coming towards the landing. Steve had gotten on the earphones with us and said, ‘Hey guys, in about 20 minutes, we’ll land. We’ll go to the bathroom and there’s gonna be a pickup truck there. We’ll jump in. Y’all want to go eat first or you want to go to the company first?’ And we said, ‘Let’s go eat.’”

Around 10:30 a.m., Steve began his descent to the Yoakum airport. The town has a population of less than 6,000, so, as you’d expect, the airport about a mile outside town is tiny. The two runways are strips of asphalt in a flat, brown, scrubby plot of land, and the markings on them are faded. There’s no control tower and no personnel on the ground. It’s meant for small planes, which is all right, because that’s what Steve had.

While the airport wasn’t a problem, the weather was. It wasn’t raining or windy, but the humidity was around 95 percent and a thick, heavy fog was sitting unusually low—in some places, it was only 100 feet above the ground.

Since it was impossible to see, Steve began his approach with the autopilot engaged. But when the plane finally broke below the clouds, probably at about 500 feet, he could see the plane was too far to the right and not lined up correctly with the runway. About a mile out, he disconnected the autopilot and began a right climbing turn so he could come around and try again.

This is when things began to go wrong. In the thick fog, the plane climbed too steeply and turned too sharply. It’s not exactly clear why.

Final segment of the flight / Courtesy of the National Transportation Safety Board“We came to this almost stop in the sky, and turned over and pitched straight down,” Kennon said. “What I’ve come to learn is we stalled, and we didn’t have the altitude necessary from our stall to recover. So when we were pitching down, we poked through that cloud cover really quickly. And right when we did, I mean, the ground was right there coming up at us really fast.”

When Kennon said they stalled, at first I thought he meant the airplane’s engine stalled, that it quit running. But that’s not what an airplane stall is.

Let me quickly explain some physics: Airplanes rise into the air because when their engines propel them forward, the air moves around their wings in such a way that pushes, and then keeps, them aloft.

When an airplane moves smoothly, gradually, up to the sky and then down again to another airport, the air is continually pushed around those wings, and the plane stays where the pilot wants it.

But when an airplane angles too rapidly, either up or down, that airflow is broken, and the plane begins to drop. Or, if a plane is moving too slowly, the airflow isn’t strong enough, and the plane begins to drop.

As Steve’s plane pitched up, it also slowed to 16 knots, or about 18 miles per hour. It was both angled too steeply and going too slowly to stay up.

To fix a stall, the pilot needs to point his nose down and step on the gas to regain that flow of air across his wings. It seems Steve did both. His plane needed 1,000 feet of air space to regain enough wind speed to level back out. And Steve didn’t have that much room.

The Crash

At this point, alarms were blaring. From the copilot seat, Tyler Patterson was calling for Steve to get the nose up, and Steve was yanking hard on the yoke.

But for all that, the atmosphere in the plane didn’t feel panicky or chaotic.

“All of this happened really quickly,” Kennon said. “If you told me I was going to be in a plane crash, I would have thought there’s not much that would be more terrifying to me than that. But there was no fear. There was definitely no panic. There was a real peace. I made eye contact with Bill. His eyes said a lot. And I just realized in that moment we were going to crash.”

The faces of Kennon’s five boys flashed before his eyes.

Kennon with his boys at the family ranch / Courtesy of Kathryn Vaughan“I just saw each one of them and just kind of breathed out, ‘Oh God, let me be there for them,’” he said. “I think that came out of me without thinking, because I love them so much, of course, but also because my dad died when I was 16, and it had been on my heart a lot lately. My oldest son was about to turn 16. . . . And then we hit. I mean, there was no time to consider anything beyond that.”

You already know this plane hit the ground with 90 times the force of gravity. The force of the impact pushed it back up. It came down again, then was pushed up again. Finally, on the third collision, it stopped.

“When we hit, I became really disoriented,” Kennon said. “My eyes were open, but the plane was spinning. Then when things got still and came into focus, it was just so, so quiet. So eerily quiet. And I was coming into my senses and realizing we had just been in a plane crash. . . . And then I looked and I could see all four of my friends.”

Dead and Dying

No one was moving.

“In the peace of that moment, I knew that they were gone,” Kennon said. “I knew not just that they had died but that they were with the Lord. I had the strangest sense in that moment in the plane that was very palpable—I was in this sacred moment. . . . I was knee to knee with my best friend and I was thinking, He is right now meeting Jesus.”

Kennon wanted to see Jesus too.

“Paul says, in Philippians 1, to depart and be with Christ is far better,” he said. “I had so many emotions. I was shocked, devastated, overwhelmed—and I had this sense of, My goodness, my buddies are entering the very presence of Christ. All that was washing over me. And then after that sacred, quiet moment, the next two things that kicked in were: I need to try to get up and get out, and I couldn’t breathe.”

The crash site / Courtesy of the National Transportation Safety BoardKennon was scared to look down at his own body, afraid of what he’d see. But his arms and legs were still attached, and nothing was obviously awry. He wasn’t even bloody.

The main problem was that he felt like the wind had been knocked out of him and he couldn’t get it back. Every 20 seconds or so, he’d get a little sip of air. He didn’t know this yet, but all his ribs had been broken and both his lungs had collapsed. Every time he breathed in, air was leaking out into his body, between his lungs and his chest wall. As it did, it decreased the amount of space available for his lungs to fill with a fresh batch of air. Kennon was slowly suffocating himself just by breathing.

Escape and Rescue

“I unbuckled and tried to crawl out,” Kennon said. “My body was kind of working with me and I pushed my lower half over the threshold. The door had blown off and so I kind of slid over onto the ground. My knee landed in a puddle of gasoline.”

This is worth noting. When they landed, the left fuel tank had broken open. Not only were Kennon’s legs in gasoline, but it was sloshed over the field. The likelihood of a fire was immense—sparks from the friction of landing, from the engine, or from the electrical system could have ignited the gasoline on the ground or the gallons still in the plane’s tanks. But it didn’t.

“I almost fell over into it,” Kennon said. “I remember thinking, If I can’t catch myself, I won’t be able to move, and I won’t make it. But I braced my forearms, and I was leaning back into the plane. I didn’t really have a plan. I was just kind of moving. And then I stopped right there and two cell phones were on the floor in front of me. And I thought, I need to call 911.”

He absolutely did. Because the plane had landed in a pasture, hidden from the road by the fog and a little hill. Nobody saw the plane go down; nobody heard the crash. Nobody was coming to help.

Kennon picked up one of the phones. It was Bill’s, and it was locked. Kennon didn’t know the password, so he put it back down.

The crash site / Courtesy of the National Transportation Safety BoardI’m going to pause here for a public service announcement. If you’re ever in an emergency situation, and you can’t get into someone’s phone, just tap or swipe it, which will bring up the screen where you can input a password. At the bottom of the screen will be an emergency button you can push to call 911. Another option is to push the power button five times rapidly.

Kennon didn’t know that then.

“I picked up the other phone,” Kennon said. “I was thinking, If this phone’s locked, this is it for me. And I turned it over. It was Tyler Springer’s phone and it was on. GPS was open. And he had been maybe looking at where we’re landing or the weather or whatever. And so I scrolled out and called 911.”

At 10:47 a.m., the 911 dispatcher picked up and asked Kennon what his emergency was. But Kennon, who had no air, couldn’t speak. She asked where he was. He was in a field about a mile and a half from the Yoakum airport, but he couldn’t tell her that. She asked what happened, and he couldn’t say anything. All he could do was groan a little. She guessed he’d been in an accident. He made a small noise.

Was it a car crash?

He made a negative sound.

A plane crash?

He tried to make a little bit louder noise.

“She stayed on the line with me,” he said. “She sent two units to the place—dispatched them to where the cell phone was sending a signal from. That gets them in the area. And sure enough, about 12 to 15 minutes later, I heard an ambulance busting through the fence line and coming down this rough terrain of the hay pasture to where I was. And then they tended to me immediately in the field.”

By “tended to,” Kennon means one of the emergency responders recognized why he couldn’t breathe and quickly inserted a needle into his back to remove the air so his lungs could expand. Later, they told him he’d probably had five minutes of air capacity left.

Immediately, the medics radioed for a helicopter to airlift Kennon to the nearest level 3 trauma center, 40 miles away in Victoria.

Sorry, the helicopter crew radioed back. We can’t fly in this fog.

Harvest Hears the News

By the time Kennon was loaded into the ambulance that would take him to Victoria, the saddle company guys waiting at the airport knew something was wrong. One of them called Steve’s wife, Cathy.

“He was screaming on the phone,” she said. “All he could say was, ‘The plane went down. The plane went down.’ And I was calm as [a] cucumber, and I said, ‘Darryl, just tell me they’re OK. So the plane went down—OK. Just tell me they’re OK.’ But all he could say was ‘The plane went down.’”

Numb with shock, Cathy couldn’t even cry. But she could use the phone. She called Kennon’s wife, Kathryn, who was at the dentist.

“I had a message from her when I got in my car,” Kathryn said. “She said, ‘Kathryn, honey, I need you to call me right away. Please call me as soon as you get this. You’ve got to call me immediately.’ And so I called her back. ‘Honey,’ she said, ‘the plane has crashed.’”

Steve and Cathy Tucker / Courtesy of Harvest ChurchKathryn couldn’t believe it.

“It hasn’t,” she told Cathy. “No, Cathy, no, it’s not. No, it’s not. The plane has not crashed.”

“Sweetheart, we don’t know any details yet,” Cathy said. “But you need to get somewhere and keep your phone on. I’m going to call you.”

Then she asked, “Can you tell me who was on that plane?”

Cathy was beginning to alert the women just in time. Yoakum isn’t a big place. Word spreads fast. And it didn’t take much longer to spread to and through Harvest.

Jamie was in his church office that day. He’d been texting the guys to see if they’d made it, and the silence was starting to make him uneasy.

“I was sitting in a meeting,” he said. “Out of nowhere, one of my really good friends, Tony Fisher—who’s the worship pastor at Harvest Church—my office door flies open and Tony’s head pops in and it’s this look on his face. You could tell he was completely disoriented. . . . And he goes, ‘My cousin just texted me that something happened in Texas.’”

At the same time, Jamie’s and Tony’s phones started to ding.

“I mean, message after message after message after message,” Jamie said. “I remember looking at Tony and saying, ‘Man, we’ve got about a three-to-five minute window before everybody out there’—and I pointed to the Harvest offices—‘before all of them start hearing stuff from people that aren’t us.’”

Tony Fisher, Bill Garner, Kennon Vaughan, and Jamie Trussell / Courtesy of Jamie TrussellTony ran through the offices, gathering all the staff.

“Everybody circled up,” Jamie said. “At this point, I don’t know actual details other than Steve’s plane has gone down. And so I told everybody, ‘Hey, look, Bill and Kennon and Steve and Tyler Springer and Tyler Patterson, they flew out for Texas this morning.’ And I looked at the staff and I said, ‘I can confirm for everyone right now, we do know that plane has crashed.’”

The reaction was immediate.

“The spectrum of sounds and emotions—it was wild in that room,” he said. “It was just combustible in that moment.”

While Jamie was talking, his phone started ringing. He ducked out, across the hall into an old choir room.

“That’s when I learned that everyone had passed away but that Kennon was the sole survivor and obviously in extremely critical condition,” he said. “I gave myself 30 seconds of crying extremely hard. And then I took a deep breath and hung up the phone because there were 30-something people waiting across the hall. And I had to go back in and let them know the details—that Bill and Steve and Tyler Springer and Tyler Patterson were with the Lord, and that Kennon was alive but in really critical condition.”

It was a terrible task.

“If I thought the first reaction was kind of otherworldly, this looked like a scene from the Old Testament,” Jamie said. “You know that idea, which we don’t really do in the West, of wailing? I mean, people made sounds that I’d never heard before. There were some members of the staff that were physically unable to stand. That was an intimate and intense moment.”

Discipleship Dividends

The staff were able to grieve for about half an hour, and then they had to get to work. Over the next hours, days, and weeks, they disseminated information, figured out which ministries to take offline and which to keep running, and wrote sermons and funeral messages. They fielded news requests and kept an eye out for people coming to look at the tragedy—sometimes literally, peering in the office windows. The staff canceled the Downline conference. They planned and conducted Bill’s funeral, then Tyler Patterson’s, then Steve’s. They drove to Denton, Texas, to help with Tyler Springer’s funeral near his family’s home. They called, stopped by, and cried with Cathy Tucker, Elizabeth Garner, and Emme Patterson.

Right away, Harvest’s culture of discipleship began to pay dividends.

Jamie Trussell at a prayer service after the plane crash / Courtesy of Harvest Church’s live stream“Discipleship in my life was normal once I came to faith, and all these little deposits that people have made along the way—all of those small deposits that have been put into your leadership bank account—all get withdrawn in a singular moment,” Jamie said. “And you realize, Oh my word, God’s put so much more there than I thought was there.”

He could see the same thing among the elders.

“I’m talking about men going, ‘I’m owning Cathy Tucker, and y’all don’t worry about a thing. I’ve got it; I’ll build the team,’” Jamie said. “And another guy going, ‘Hey, Emme’s worked in my vet clinics for years. I’m owning Emme. And don’t worry about a thing.’ And another guy going, ‘I’ll be at Kathryn’s house every day when the kids get home from school.’

“I’m not advocating for any ecclesiological model necessarily, but we don’t do it to that degree without a plurality of elders. We just don’t. And that was such a gift because you trusted those men were going to do fantastic at that. And they were stepping into hard stuff. By the way, these aren’t staffers. These are finance guys and CEOs and whatever else. They are just godly men who took their role seriously and immediately stepped in.”

The fruit of discipleship didn’t stop there.

“The people of Harvest shined toward one another and toward us in ways that they hadn’t had to before,” Jamie said. “And you never really know until you’re in it what something like that will do for your church. But here’s this strange paradox of Christianity—our church thrived and was vibrant and joyful while also lamenting and grieving in unprecedented ways.”

Church members prepared food, took care of children, and made phone calls. They helped with the funerals, wept with the families, and donated money to help with the kids’ education. They prayed together, sang together, and shared Scripture with each other. Most of all, they were together—at church or at the houses of the women.

And the whole time, they were waiting for word on Kennon.

In Surgery

After the crash, Kennon traveled by ambulance to Victoria, which immediately sent him on to Brooke Army Medical Center, a level 1 trauma center in San Antonio. Jordan Guice was his surgeon.

“He took quite a shot,” Guice said. “That vector of force that went through his right upper quadrant was tremendous. Angled up a little bit, his liver would have been cracked completely. I mean, his liver had cracks and holes, but it would have been cracked completely. He probably would have bled and died in the plane. Angled more towards the center—his aorta was right there. I mean, he had a devastating injury, but if the vectors of force had been just a little bit off—a few centimeters here and there—he wouldn’t be here. That was pretty amazing.”

Jordan Guice and Kennon in San Antonio / Courtesy of Jordan GuiceEven with a good vector of force, Kennon’s insides were a mess. Two of his ribs had broken clean off and were floating around. His kidneys and liver were shredded. One of his collapsed lungs was punctured. There was a two-inch hole through his diaphragm. Two-thirds of his colon was in such bad shape that it had to be removed.

Throughout several hours of surgery, Guice took Kennon’s organs out one by one and repaired them.

“We call it damage control surgery,” he said. “Basically, you stop the immediate life-threatening things first and assess how he’s doing. . . . As we were doing the dissection for the colon, I remember that we saw a little bit of bile. Bile is the stuff that drains from the liver into the small intestine through a tube called the common bile duct.”

Guice looked up at his chief resident, Connor.

“We both looked at each other and looked down at it,” he said. “It was just a small amount. We both kind of smiled, and I remember saying, ‘Man, that’d be bad.’ And I just put a lap pad—a piece of cloth basically that helps suck up blood and stuff—right there and I was like, ‘We’ll come back. Let’s finish what we’re doing.’”

Guice and Connor put Kennon’s colon back together. They fixed his diaphragm. They put some chest tubes in. A couple hours later, they came back to the bile problem.

“There was a large amount of bile now,” Guice said. “At this point, me and Connor were like, ‘This is a problem.’”

It was a huge problem, not only because Kennon needed that bile to have a way to move from his liver into his intestines to digest his food, but also because bile that’s floating around in your abdomen will damage or infect the other organs. You can live without your appendix, but you cannot live without some kind of bile duct. And Kennon’s had disappeared.

Diagram of the abdomen / Courtesy of pueblo.gsa.govAll Guice could find was one end of it, which was in itself amazing because the bile duct is only five millimeters in diameter. In fact, it’s so small and so well insulated with fat and organs that it hardly ever gets injured. When Guice presented Kennon’s case later to a worldwide gathering of military doctors, nobody had ever seen anything like it. In the operating room, when Guice called for backup, his superiors had never seen it either. While Kennon was still on the operating table, they did some research and found bile duct replacements had been done fewer than 20 times. In those cases, surgeons had tried basically three different strategies to fix it. None was great—all led to complications later.

Finally, Guice MacGyvered an answer. He skipped the bile duct altogether, attaching Kennon’s liver directly to his small intestine. Then he sewed Kennon back up.

“I thought we were going to be in for a really long hospitalization with a lot of complications,” he said.

Instead, Kennon would be out of the hospital and back home in just three weeks. There weren’t complications—at least, not physical ones.

He Is or He Ain’t

A few days later, Kennon was sitting up in bed for the first time. His pain was stable, and he was able to think.

“I still couldn’t believe what had happened,” he said. “I was thinking about how those men were gone, and the reality and the gravity and the finality of their earthly death. I got real emotional. I just started crying—just my own longing to see them. And then I was thinking that I invited every single one of those guys.

“I started thinking, If only Bill had gone on one of the other [trips] or if I hadn’t invited him . . . he wouldn’t have been on this one. Why did I invite Tyler [Springer] to come with us? He had his own plans. He would have done just fine. And I invited him to come with us and said we’d drop him off in Dallas. And it seemed like such a good idea. And I wish I’d just gone to get a coffee with Tyler Patterson. Everything made me go, Why, why, why. If only I had not done this.”

Just then, there was a knock on the door. A hospital employee stuck his head in.

“Dr. Vaughan, would this be a bad time for guests?” he asked.

“Yes, I can’t see any right now,” said Kennon, who was “just a mess.”

“OK, well, I just wanted to let you know that a Soup Campbell and Steve Winstead were here to see you,” the man said.

“Wait a minute, wait a minute,” Kennon said. “Hold on, yeah, let those guys in.”

Soup and Kennon / Courtesy of Kathryn VaughanThey came in, and Kennon tried to pull himself together and wipe his face.

“They sat down, and Soup was right there at my bedside, right at my arm, and Steve was at my feet,” Kennon said. “I just lost it again. I started bawling, and I started saying the same things I’d been saying in my head. I was saying them out loud: ‘Man, I’m the one that invited every one of them. I wish I hadn’t said that. I didn’t even see Tyler until Sunday morning.’”

Soup stopped him.

“He put his hand right on my knee, and he said, ‘Look at me,’” Kennon remembers. “I was just a blurry mess. I looked at him and he said, ‘Look, man, he is or he ain’t. You feel me?’

“What? No, what?”

“He is or he ain’t,” Soup repeated. “Either God is sovereign over every single bit of this thing or he ain’t sovereign at all. . . . You’ve preached several times, you’ve studied the Word, and you know about God’s supremacy and his sovereignty. So is he is or is he is not? That’s the only question.”

Soup remembers Kennon’s expression changed.

“I call that phrase to mind pretty much every day,” Kennon said. “There’s always times that I get overwhelmed with that loneliness and that heaviness. And I just have to say to myself, He is or he ain’t. And I believe he is. And that’s an area I gotta trust him with.”

Why?

It’s impossible for us to know the mind of God, to ever say, “This is why God allowed this certain tragedy to happen.” That line of thinking leads to a logical quagmire. For example, we could say God allowed Kennon to live so his boys would have their dad. But what about Tyler Patterson’s kids? Why do they have to grow up without theirs? Or we could say God allowed this to happen so people could hear the gospel proclaimed during the funerals. But couldn’t the Lord have reached those people another way? Of course he could have.

A more fruitful train of thought, then, is to acknowledge that while we’re on this earth, we’ll never know why God prevents specific tragedies and allows others.

But we do know this: He never leaves us.

Elizabeth Garner, Bill’s wife, was a young widow when he married her. She was on a trip with friends when she got the news.

Bill and Elizabeth Garner in Zion National Park / Courtesy of Elizabeth Garner“I was on the way to the airport when my dad called me,” Elizabeth said. “I remember exactly what he said. He said, ‘Elizabeth, this is Daddy. I’m so sorry. Bill was killed in a plane crash.’ And I felt like the walls of this SUV were caving in on me, and all I could think was, Lord, I cannot do this again. My children can’t do this again. But [God’s] grace has been sufficient every day, even in the midst of unthinkable suffering and pain. And since January of ’23, the Lord has actually filled my life abundantly. He’s sustained me; he’s comforted me; he’s provided me with a new community and a college town with opportunities to share about his faithfulness, his love, his goodness, his mercy, even in the wake of tragedy.”

Emme Patterson also found light in the darkness.

“In what has been the most painful 13 days of my life, there’s been a surprise—I have found joy,” she said at Tyler’s funeral. “My heavenly Father has left zero doubt in my mind that Tyler Patterson was supposed to be in that airplane on January 17. He orchestrated too many critical details—and sweetly gave me knowledge of those—to make this trip possible for Tyler. We prayed over this trip on Sunday—not for safety but that God would be glorified through this trip and through these men.”

Tyler and Emme Patterson and their children, Elsie and JB / Courtesy of Harvest ChurchA brand-new widow with two toddlers, Emme said she woke up each morning with a new lie in her head: You’ve lost your helper. You’ve lost your friend. You can’t do this by yourself.

“The Lord has answered each of these lies with truth, whether it was by the obedience of fellow believers or through his Word, which I’ve clung to for the past two weeks,” she said.

The Lord sustained Cathy Tucker in part through a new friendship with an older woman, Becky Cook, who also lost her husband. They talk or see each other nearly every day.

And on Sundays, Cathy sings with the worship team.

“The whole first year, I was paralyzed,” said Cathy, who hangs on to Isaiah 49:13. “I was paralyzed physically. I was paralyzed mentally. I would either be on the sofa downstairs or in my bed, just curled up like a fetus in the womb. And it was just unreal, you know? But then on Sundays, it was time for me to go sing, and they would just let me show up and sing with the group.”

On Easter this year, Tyler Springer’s parents shared a message with their church.

“God called me out,” his father, Brad, said. “He took me to the valley. And then I believe I felt the breath of God come upon me, and peace like a river flowed through my life because I still believe. Yes, we’ve lost Tyler. Yes, we’ve lost a big chunk of our life. But do we really believe that Jesus Christ came and died for our sins and that we have an eternal destiny? Do we really believe that? Do we believe this is it here on earth?

Tyler Springer with his parents, Brad and Denise / Courtesy of Lindsay Springer Rose“I’m blessed to be able to go that deep with God and to see how God’s at work. Whatever tragedy is happening in your life, I want you to bow and ask God to use that tragedy for his glory. And I believe that he will—maybe in a big way, maybe in a small way, but always know that God is going to be there for you. He is for you and not against you.”

The First Fruits

It’s a comfort to know the Lord’s presence in times of tragedy. But sometimes, in his grace, he gives us even more, and we can start to see him working things together for good (Rom. 8:28).

About a week after the surgery, Guice visited Kennon’s hospital room. He was finding it hard to believe that Kennon had survived not only the crash but also the surgery with no physical complications.

“He comes in, and it was the first time I’d ever seen his face,” Kennon said. “He took off his surgeon mask. He pulled it back and flipped it towards the trash can. And he said, ‘Tell me your story.’”

Kennon was confused. “Do you mean how I’m feeling? Or what hurts?” he asked.

“Your story,” Guice said. “I want to hear your story.”

So Kennon gave him his testimony.

“And at the end of it, he was contemplating what I was saying,” Kennon said. “And I said, ‘Hey, are you a Christian?’”

“I can’t say that I am,” Guice said.

“You know, doc, I don’t know that I would say it this way to be theologically precise, but maybe God used you to save my life and maybe he’s gonna use me to save your life,” Kennon said.

“I think you’re right,” Guice said.

“And I was like, Whoa,” Kennnon said. “I remember the sweetness of that moment and thinking a week or so in, It’s just some little tangible fruit that God’s going to redeem this. God’s gonna bring salvation.”

The Second Fruits

Kennon got another glimpse of that around Memorial Day 2024, nearly a year and a half after the accident. He was in Texas for Tyler Springer’s memorial service, and he asked the owners of the pasture where the plane crashed, Mitch and Larissa Harbus, if his family could stop by to see it. Mitch and Larissa said sure.

They all went down to the pasture together, where they listened to Kennon tell what he could remember, cried, prayed, and added to the memorials Mitch and Larissa had erected.

Mitch and Larissa Harbus / Courtesy of Larissa HarbusThen Larissa shared that while she and Mitch were both raised Catholic, when they’d watched the live-streamed funerals of the four men who died on their land, they’d been struck by the personal way everyone who spoke talked about knowing the Lord. She and Mitch came to a conclusion: “We want to know Jesus like these men did.”

“I have actually always told myself, even way before this happened, I wish you could buy CliffsNotes on the Bible,” Larissa said. “I wish somebody would just sit down and explain some of that stuff. Some of that is so confusing to me. Catholics preach the gospel, but we’re not one of those gospel-driven churches. So I don’t get that explanation in my Mass or my homilies. And so it was like I was missing it. . . . Just talking to [Kennon] about a few things out here in the pasture—he was explaining more to me in minutes than I had understood all my life.”

Larissa signed up for Downline, where she’s learning the story of the whole Bible. Even though he isn’t an official student, Mitch is learning too.

“And even Mitch is like, ‘Wow, the way they profess it—it’s easy to understand. And it just has so much meaning and value,’” she said. “Little things that we just didn’t even know or pick up on—I read the book of Ruth before, but I never understood it until Kennon explained it in like four sessions. He explained the book of Ruth, and now I totally understand.”

While they were still standing in that pasture together, Larissa said to Kennon, “Hey, Mitch and I do not think that plane crashed on our land on accident. Do you want to build a church here? On our land? In this pasture? We think God may want the gospel to go forth right here.”

“I’m looking around, and there’s not a structure in sight,” Kennon said. “And it’s so beautiful and so crazy.”

“Larissa,” he said, ‘‘I don’t know what to say. Who would come to church?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “But there’s gotta be others.”

A week later, Kennon was back home, cutting and stacking firewood with one of his mentors.

“You know, the craziest thing happened,” Kennon said. He told him what Larissa had said. “I mean, we wouldn’t actually plant a church in that field, right? I’m real big on all the things that Tim Keller’s written about—you know, trying to plant churches in populated areas. Makes a lot of sense.”

“Well, I don’t know,” Kennon’s mentor said. “I mean, the plane crashed there. And these people are saying God awakened them to a desire to know him through it. They think there’s others. She wants the gospel preached. Hey, let’s preach the gospel there.”

The Harvest

On January 17 and 18, 2025—two years to the day after the plane crash—Kennon preached a revival-style meeting in that field in Texas. Ellie Holcomb, whose husband is Emme Patterson’s cousin, sang. So did Aaron Watson, who had recently connected with the new owner of Steve Tucker’s saddle company. Two hundred Harvest members drove the 11 hours to volunteer. Another 200 members came just to be part of it.

In the end, the weather wasn’t great. It was windy and cold.

But nearly 4,000 people came.

Revival in the pasture / Courtesy of Kathryn Vaughan“We saw over a hundred people commit their lives to Christ,” Kennon said. “We have cards they filled out. We had a whole lot of communication—encouraging things about how God was setting them free from addiction or bringing them back to faith that had grown dead, or coming to Christ for the first time. I just poured through those, thinking of my buddies and thinking, God will not waste an ounce of our suffering. Before the ages began, God knew each one of these stories. And the first fruits of Dr. Guice and of Mitch and Larissa all of a sudden turned into this incredible harvest.”

Steve, Tyler, Bill, and Tyler didn’t die so those people would be saved. Jesus did that.

But in the fullness of time, the Lord called those men home. And in the fullness of time, he used their deaths to bring others to himself. Here’s how Soup thinks about it: “They weren’t martyred for their faith, but their faith was planted, just like a martyr’s life would be planted,” Soup said. “Their faith was planted. So these guys’ lives are still ministering—and will be for a long time.”

Two Years Later

It’s been more than two years now. Emme Patterson just got remarried—the Lord has provided another father figure for her little ones. Elizabeth Garner’s daughter attends Auburn University, where Elizabeth has found renewed purpose discipling young women in her church. She’s actively working to establish a Downline Institute in Auburn.

Tyler Springer’s parents, three brothers, and sister have grieved together and been knit closer by the tragedy. And the baby he was flying to see? They named him Tyler.

Guice is deployed to the United Arab Emirates. Before he left, he visited Harvest Church and heard Kennon tell the story about Soup’s question: Is he or ain’t he?

“That’s really the one part that I really remember and think about,” he said. “There’s a saying in trauma: ‘I didn’t shoot him. I didn’t wreck his car. I didn’t cause him to get drunk and drive into a tree.’ Bad things happen. Patients die. I think we have to be a little bit impersonal to be able to do the job.”

Soup’s question changed that, he said. “Maybe I should reframe that and be like, ‘God is sovereign and this happened for God’s plan.’”

Kennon’s boys are growing up, and his marriage is sweeter than ever. After Kennon was able to retake the reins at Harvest, Jamie Trussell moved two hours northwest of Yoakum to a small town called Dripping Springs, where he’s leading a church revitalization.

Larissa continues to work her way through Downline classes. She and Mitch are still lobbying for a gospel-preaching church in Yoakum.

“We’ve actually started two live Downline Institutes within a half hour from there,” Kennon said. “One’s serving the Shiner/Yoakum area in Shiner, right up the road. And another one’s 25 minutes away in Gonzales. We’ve got over 100 people right now—some that don’t have a church, some that are from rural churches in that area that are saying, ‘Hey, we want to know God like those men knew God.’ And we’re teaching them the Bible.”

Of course they are. At Harvest Church in Memphis, that’s what they do. For the past decade, they’ve been showing up to early morning Bible studies, evening small groups, and Saturday coffees at church, in restaurants, or at each other’s houses. They’ve been asking each other, “Can I get some time with you?” Day by day, week by week, they’ve been pushing each other into a deeper understanding of the Bible, a deeper knowledge of their own sin and sanctification, a deeper walk with the Lord.

Kathryn Vaughan (left) and her discipleship group / Courtesy of Kathryn VaughanAnd when their storm came, like it does for everyone, they cried to a God they knew would comfort them. They asked why, but they didn’t actually need an answer, because they trusted the good will of their Father in heaven. They raged against the brokenness of a world where this could happen—and then trusted in a sovereign Lord who would one day put things right.

And then, because this was the rhythm of their lives, they went to church and sang with Cathy “When Peace like a River” and “Yet Not I but Through Christ in Me.” They listened to sermons from Jamie Trussell, whom the Lord spared. They got with their small groups and one-on-one mentors to pray and talk and read the Bible.

The Friday after Steve’s funeral, Cathy woke up to find the men from his discipleship group parked in her driveway—just like they’d done for years and years.

“What are you doing here?” she asked them.

“We didn’t know where else to be,” they told her.

She told them to come in, and to this day—more than two years after his death—Steve Tucker’s discipleship group still meets in his home every Friday morning. They read the Bible, drink coffee, talk, laugh, and pray.

Cathy told them they were always welcome and gave them a key. “Don’t stop,” she told them. “I hope you don’t stop until Jesus comes back.”

Popular Products

-

Devil Horn Headband

Devil Horn Headband$25.99$11.78 -

WiFi Smart Video Doorbell Camera with...

WiFi Smart Video Doorbell Camera with...$61.56$30.78 -

Smart GPS Waterproof Mini Pet Tracker

Smart GPS Waterproof Mini Pet Tracker$59.56$29.78 -

Unisex Adjustable Back Posture Corrector

Unisex Adjustable Back Posture Corrector$71.56$35.78 -

Smart Bluetooth Aroma Diffuser

Smart Bluetooth Aroma Diffuser$585.56$292.87