How Capitol Hill Baptist Church’s First Pastor Changed His Mind On Slavery And Became An Abolitionist

On a crisp Virginia morning in September 1831, Joseph W. Parker sat across from Nicholas Sterling Edmunds, the owner of the nearly 2,000-acre Homewood plantation. Parker had spent the past two years as a schoolteacher for Edmunds’s children while simultaneously ministering to and evangelizing Edmunds’s slaves. He had seen remarkable spiritual fruit—both within Edmunds’s family and among the enslaved people. The faith of one of these newly converted slaves shone so brightly that his owner was forced to admit, “If my hope of heaven were half as bright as my confidence that John is fit for it, I should be a much happier man than I am.”

Now everything was about to change.

A month earlier, Nat Turner’s rebellion had erupted in Southampton County, barely a hundred miles away. The brutal uprising sent shockwaves through Virginia’s white planter class, stoking fears of insurrection and revenge. In response, state legislators passed new draconian laws to suppress education and religious instruction among the enslaved population. As these anxieties gripped Homewood, Edmunds quietly but firmly informed Parker across the breakfast table that morning, “You must stop religiously instructing my slaves.”

Parker was taken aback. “Do you believe that John is a true Christian?” he pressed. “Is he a worse slave than before?”

“He is entirely faithful,” Edmunds admitted. “But he feels himself . . .” Edmunds paused, searching for the right words. “He feels himself a man accountable to God. When Isaac was buried the other day,” Edmunds continued, gaining momentum as he spoke, “I heard John exhorting his fellow servants to prepare to meet their God. You see, John understands that what God requires of a man and what a master requires of a slave are two very different things. So you must stop instructing my slaves.”

Undeterred, Parker continued to press Edmunds. “Do you believe that Jesus Christ has given us a system of religion which has bidden us to preach to every creature which is dangerous for all to be instructed in?”

“We can’t philosophize on that subject,” snapped Edmunds, “but suppose you go down to the slave quarter tonight and read that part of the sermon on the mount which says, ‘Therefore, whatsoever ye would have men do to you, do ye even so to them,’ and you explain it and talk to them of all the excellence of this precept, and so on. Have I a single man on the plantation so dull that he will not stop and say, ‘If you please, sir, does Master Nicholas treat us as he would have us treat him?’ You must answer them. Now if you say ‘Yes,’ they know you lie and you can do them no good. But if you say, ‘No,’ you damage my character among them. I tell you sir, we can do nothing toward giving Christian light and instruction. We are bound to keep them as dark as possible. You must desist from teaching them at all.”

At this, Parker’s heart stirred. “Can you stand the full blaze of the light of salvation through Jesus Christ and rejoice for yourself and your family, while you shut it entirely from those absolutely dependent on you?” he asked Edmunds, his voice thick with emotion.

Edmunds turned pale. “For God’s sake, Mr. Parker,” he whispered, “don’t name the day of judgment in connection with slavery. But you must desist from teaching my slaves.”

That night, Parker wrestled with what he had seen and heard. He could no longer ignore the obvious truth. “Slavery seemed to me,” he later wrote, “an outrage upon the rights of man.”

Not long after that fateful exchange with Edmunds, Parker was abruptly informed that he must immediately leave the Homewood plantation and return to New England. Without a chance to say goodbye to the slaves and children he had grown to love, he packed his bags and headed north, grieving but determined to do what was within his power to oppose the system of race-based slavery.

Parker’s Transformation

I first read this exchange—recounted here nearly verbatim—in an unpublished memoir of Joseph Parker collecting dust in the University of Virginia Library’s special collections while I was writing a history of Capitol Hill Baptist Church in Washington, DC, which would eventually call Parker as its first pastor. What emerged was a previously unknown portrait of Parker’s journey from fairly moderate views (slavery was an unfortunate but necessary institution) to a more biblical conviction that race-based slavery was evil and opposed to Scripture.

Parker moved from fairly moderate views to a more biblical conviction that race-based slavery was evil and opposed to Scripture.

Returning north with his heart increasingly drawn to ministry, Parker enrolled at Newton Theological Institution. Every Saturday, he walked eight miles to Boston to teach a Sunday school for African Americans, going door-to-door to minister among their families. Parker later reflected on the effect of these visits: “My views on race gradually changed. I saw that it was wrong to hold them in bondage, to regard and treat them as chattels, or to buy and sell them as brute beasts. I found myself, most unexpectedly, an antislavery man.”

In May 1837, Parker served as a delegate for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. “For several years, my mind had been settled on the conclusion that we were within the marginal whirl of the maelstrom of a fearful revolution brought on by slavery,” he later wrote. “I knew slavery or the nation must perish, and the struggle for the life of either would be terrible. I saw this as clearly as an event already past.”

By this time, Parker’s antislavery stance was well known. Proslavery advocates vilified him as a “rabid abolitionist,” while radical antislavery voices criticized him for being “not radical enough.” Such was the precarious position of a minister in those turbulent days.

Education for Former Slaves

Parker had built a thriving ministry at First Baptist Church of Cambridge, Massachusetts. However, with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, he was confronted with the suffering of newly freed African Americans—men, women, and children who had escaped slavery and now sought refuge behind Union lines. These displaced individuals, known as “contrabands,” urgently needed shelter, food, and, above all, education.

Parker’s pivotal experience in the South as a young man and influence within the Baptist denomination made him an ideal leader for a new mission: to provide schools, resources, and pastoral care to freedmen across the war-torn South.

For the next five years, Parker gave himself tirelessly to this work, crisscrossing the Atlantic states, recruiting teachers and preachers, and establishing schools in cities like Alexandria, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Beaufort, and Richmond. Moving with the Union army, he took charge of vacant and abandoned churches, transforming them into classrooms and places of worship for black congregations.

Whenever possible, he worked to reclaim church buildings from military occupation. On one occasion, Parker approached a military surgeon who had converted a church into a makeshift hospital and ordered him to vacate. The surgeon, frustrated at the request, sneered, “Why, you are a sort of pope, aren’t you?” Without missing a beat, Parker responded, “Yes, a Christian minister and military pope. Go!” The church was returned to its original purpose—to proclaim Christ’s name and serve his people.

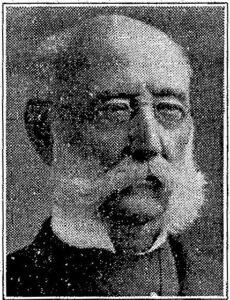

Joseph W. Parker in the 1870s. Parker (1805–87) pastored two of Boston’s most prominent churches before resigning to coordinate the work of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society among former slaves during the Civil War. He also served as the first pastor of Capitol Hill Baptist.Parker’s work frequently brought him to Washington, DC, where he founded the school that would later become Wayland Seminary—a key institution in the education of African American ministers and leaders. He also became a familiar figure in the city’s Baptist circles, including among the future members of a church of which he would become the first pastor.

After years of ministry and a brief season of recuperation on his Maryland farm, Parker had resolved never to pastor again. But when representatives from the newly formed Metropolitan Baptist Church (later Capitol Hill Baptist Church) pleaded with him to lead them, he couldn’t ignore their need.

Despite the church’s meager resources—offering him only half his previous salary—Parker accepted the call as a matter of duty, believing the church’s future would be jeopardized without experienced pastoral care. His ministry at Metropolitan—his final full-time pastorate—provided the stability needed by a fledgling church, which would continue his legacy of faithfulness to the gospel.

Incompatibility of Christianity and Slavery

Parker lived at a moment when the battle lines over slavery were being drawn more sharply than ever. Some proslavery theologians sought to defend the institution, while abolitionists marshaled biblical arguments for its end. Parker’s journey, however, illustrates the fundamental incompatibility of Christianity and slavery. At first, he accepted the common assumption that slavery was an unfortunate but entrenched institution. But his firsthand encounters with slavery’s pernicious effects forced him to question that assumption.

Parker was convinced that Christianity required that the gospel be preached to all people—none excluded (Matt. 28:18–20). But that very proclamation was forbidden under slavery because Christianity also demands that those who embrace the gospel be treated as brothers and sisters in Christ (Gal. 3:28).

Parker was convinced that Christianity required that the gospel be preached to all people—none excluded.

This was precisely what Edmunds and other slavery proponents feared. They understood that a Christianized enslaved person would become something more than property—he would come to realize both his accountability to God and the equal worth of his soul before God. To teach the enslaved to read the Bible was to invite them to see their true dignity. To preach the gospel was to plant the seeds of freedom.

The earliest known photograph of Metropolitan Baptist Church’s first building, completed in 1876 and demolished in 1911 to construct the present building. This is the only building that Joseph Parker, on arriving in 1879, would have known. Photo from the Capitol Hill Baptist Church Archives, Washington, DC. Used with permission.This is why race-based slavery and Christianity cannot coexist—at least not for long. Slavery existed long before Christianity, but Christianity provided the moral and theological resources to secure slavery’s demise. As historian Rodney Stark has observed, “Of all the world’s religions, including the three great monotheisms, only in Christianity did the idea develop that slavery was sinful and must be abolished . . . only in the West did significant moral opposition ever arise and lead to abolition.”

Parker’s life exemplified this slow but unstoppable transformation. He didn’t set out to be an abolitionist. Yet through his commitment to Scripture, his zeal for gospel advance, and his love for those made in God’s image, he found the courage to stand for the truth. In doing so, he left an example that continues to inspire today.

Popular Products

-

Classic Oversized Teddy Bear

Classic Oversized Teddy Bear$25.78 -

Gem's Ballet Natural Garnet Gemstone ...

Gem's Ballet Natural Garnet Gemstone ...$206.99$85.78 -

-

Butt Lifting Body Shaper Shorts

Butt Lifting Body Shaper Shorts$80.99$47.78 -

Slimming Waist Trainer & Thigh Trimmer

Slimming Waist Trainer & Thigh Trimmer$57.99$39.78