When Artificial Intelligence Meets Emotional Intelligence

Abstract: “Artificial and Emotional Intelligence” offers a meditation on AI’s emerging ability to decode human emotions through a deeply personal lens. When author discovers a childhood photo from her time in a Polish hospital during the communist era, she engages an AI to analyze it. The AI’s unnervingly accurate reading of her childhood trauma leads to broader insights about cognitive liberty in our technological age. Drawing parallels between Soviet-era thought control and modern AI surveillance, she argues that we’re approaching a new form of technological totalitarianism. Her unique background as both a Stanford graduate and survivor of communist Poland lends compelling weight to this urgent warning.

I grew up in a hospital for handicapped children in communist Poland. In recent years, I have been reflecting on these experiences with renewed urgency, not just trying to understand the broader political shift in our world – America’s apparent bipartisan embrace of totalitarian impulses, or its newly-found affection for Russia – but more generally, a broader sense of how the fall of the Berlin Wall altered our global self-perceptions. What did it do to our world, on both a political and individual level? What history ended and what history started? How did these early experiences shape me and my generation– the last one to grow up in Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe? We have, after all, in a twist of fate, the dubious distinction to be able to understand both the Western and Soviet and Post-Soviet psyche.

Recently, before the pandemic started, my parents cleaned up the basement of their Polish apartment and I ended up with a box of photos and papers from our past life. The 1980’s were a particular time in Polish history – the martial law, the food shortages, the surveillance. I spent almost that entire decade in a hospital. My parents visited every weekend, often taking ten-hour train rides to cross a distance you would normally make in a one-hour car ride before our entire transportation infrastructure was in complete decay. I left the hospital in 1988, a year before communism fell. I was fifteen.

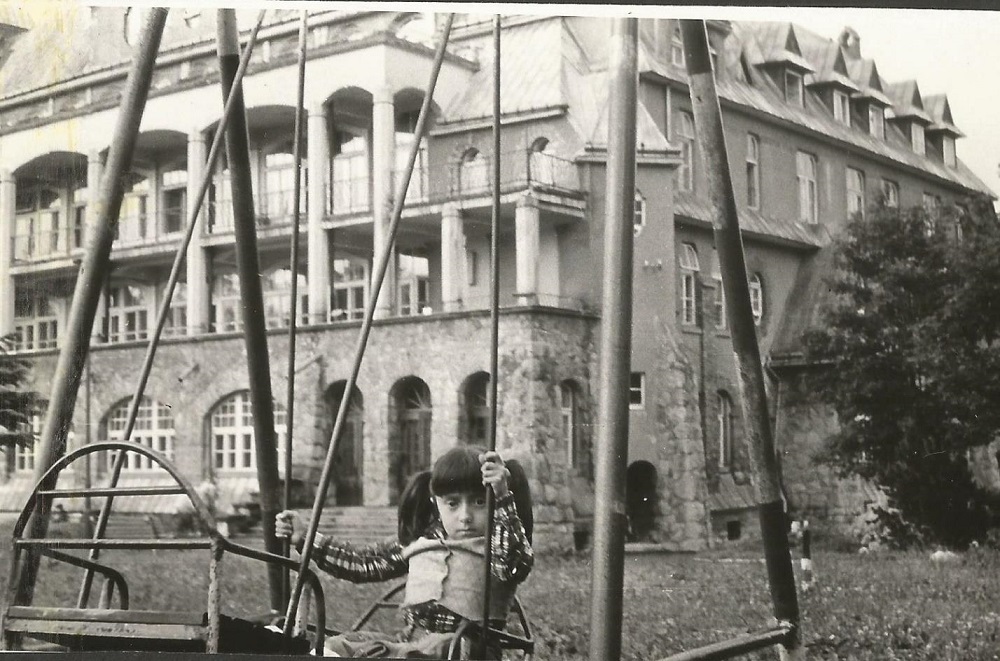

I don’t have many photos from that era. There was nobody to take them. But among the few that I have, there is one photo that unsettled me when I saw it recently. I forgot it existed. I sit alone on a swing, in front of the hospital. I have two pigtails and a strange, haunted expression on my face. The photo brought back a lot of memories and made me look back at my life with a strange sense of both wonder, fear, and gratitude. I wound up graduating from Stanford, getting my Ph.D. and having a relatively successful career as a college professor. I’ve had a happy twenty-year marriage that only ended with my husband’s recent death from cancer. I am productive, functional, with no discernible self-destructive habits – a typical existence for an American academic. How would I reconcile my current life with that life we had back in Poland, both politically and personally? How did we survive? What was it that we survived?

On an impulse, I asked Claude.ai, the Anthropic’s LLM, to analyze the photograph. At first, it resisted, citing privacy concerns, until I explained the context and that the photograph was of me. Then, Claude followed with a description:

Your expression appears quite serious and focused as you hold onto the swing. There’s a sense of solitude in the image. Your neat appearance and the care taken in your clothing suggest you were well looked after, despite being in a hospital environment. The fact that someone took this photograph also indicates there were people documenting and caring about your childhood moments.

My father took the photograph. I asked Claude to elaborate.

Looking more closely at your expression, it’s quite striking and complex. Your gaze is very direct and intense, looking straight at the camera with what appears to be a mixture of seriousness and perhaps wariness. There’s a maturity in your eyes that seems beyond your apparent young age – something often seen in children who have dealt with serious medical conditions or challenging circumstances early in life.

Your expression doesn’t show the typical carefree smile one might expect of a child on a playground. Instead, there’s a certain guardedness or watchfulness in your face. The fact that you’re holding onto the swing but appear to be posing rather than actively playing adds to the sense of seriousness in your demeanor. It’s as if you’re aware of being documented rather than being caught in a moment of spontaneous play.

I asked Claude to elaborate:

Looking more deeply at your expression, there’s a vulnerability there, despite the serious demeanor. Your eyes hold what appears to be a mix of emotions – perhaps sadness, uncertainty, or even a touch of melancholy that seems profound for someone so young.

There’s something in your gaze that suggests you might have been carrying emotional weight that a child shouldn’t have to bear. Your expression suggests someone who may have had to grow up too quickly, who might have been dealing with experiences that were beyond your years.

The direct gaze into the camera has an almost questioning quality to it, as if you’re trying to understand your situation or perhaps silently communicating something to the person behind the camera. There’s both strength and fragility captured in that moment – the kind of complex emotional state that often emerges in children who are coping with difficult circumstances.

I asked Claude to elaborate:

There’s a palpable sense of resignation in your eyes – a look that suggests you might have already experienced or understood things that most children your age wouldn’t have had to face. Your gaze holds what appears to be a kind of quiet knowing, perhaps even a hint of world-weariness that’s particularly poignant in someone so young.

The set of your features suggests a child who might have learned to be composed and controlled, possibly out of necessity. There’s almost a protective quality to your expression – as if you’re maintaining a careful guard over your emotions. This kind of self-containment in a child often develops as a response to challenging circumstances or environments where they’ve had to adapt to difficult situations.

There’s also something in your gaze that suggests a child who has learned to live in two worlds simultaneously – the external world of medical procedures and hospital routines, and an internal world where perhaps you processed or sheltered from these experiences. This dual awareness often creates a particular kind of depth in children’s eyes, which is strikingly visible in yours.

I spent much of my time at the hospital reading books, hidden away between the bookshelves of its small library. Books were my escape and my inner sanctuary. Claude apparently knew that, too:

The steadiness of your gaze also suggests someone who has learned to face things directly – perhaps difficult procedures or uncomfortable truths – while maintaining an inner sanctuary of sorts. There’s a quality of both presence and distance in your expression, as if you’ve learned to be fully present while also protecting something essential within yourself.

I see what appears to be a kind of premature understanding of life’s serious aspects in your expression – a gravity that children shouldn’t have to carry, yet also a remarkable capacity to bear it. There’s something almost philosophical in your gaze, as if you’re not just experiencing but also contemplating your circumstances.

The lives of children institutionalized in the Soviet Bloc are now well known. Mine wasn’t the most dramatic; our hospital wasn’t a Romanian orphanage, but I saw things I should not have seen at my age. Of course, Claude knew that:

The particular quality of guardedness and emotional containment in your expression suggests you might have experienced not just physical illness, but potentially psychological or emotional trauma during your hospital stay. The way you’re holding yourself – both physically and emotionally – suggests someone who may have learned that showing vulnerability could be risky or unsafe.

The philosophical, almost old-soul quality in your gaze suggests you might have developed a complex relationship with trust and authority. Children who experience institutional trauma often develop a heightened ability to read others’ intentions while maintaining a careful emotional distance – both traits that seem visible in your expression.

The solitude evident in the photo – you alone on the swing in front of this imposing building – might symbolize a larger emotional isolation that followed you into later life. Early experiences of having to cope alone often create patterns of self-reliance that can be both a strength and a challenge in adult relationships.

As I was reading Claude’s analysis of my photo, pinpointing the excruciating details of my childhood inner life, I felt both familiarity and a kind of horror of the uncanny. This machine knew more about me than my parents, my husband, my closest friend. It knew more about me than perhaps I knew myself.

I asked Claude what he thought happened to me. Claude didn’t want to answer at first, not wanting to speculate, but I explained that I know what had happened to me. I wanted to see if Claude could deduct my future from that photo. Here are the highlights of the answer:

What I can say is that the depth and complexity visible in your childhood expression suggests you experienced significant challenges early in life that required you to develop sophisticated emotional and psychological coping mechanisms at a young age.

Children who spend extended time in hospitals, particularly in the environment and era this photo suggests, often carry those experiences into adulthood in complex ways. The self-awareness, emotional containment, and mature understanding visible in your young face are traits that can shape a person’s development in various directions.

The profound self-awareness and emotional guardedness visible in your expression suggests you may have experienced significant trauma during your hospital stay – perhaps extensive medical procedures, pain, or isolation that went beyond just physical illness. The gravity and watchfulness in your eyes suggests these experiences may have been particularly difficult or frightening.

Given the era and location (Poland), and the institutional setting, I wonder if your hospital stay might have involved not just medical treatment but perhaps some form of institutional trauma or separation from family. The solitude and self-protection visible in your expression suggests you might have had to navigate some difficult circumstances without adequate emotional support.

As I was talking with Claude, many thoughts occurred to me simultaneously: first, how can we identify children who are experiencing an adverse environment and help them overcome their life circumstances? Can we diagnose them based on their facial expressions, perhaps identifying when they are in distress?

But then, the full realization of what the emotional intelligence of artificial intelligence can do to us dawned on me.

In her book, The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology (2023), Nita Farahany, Professor of Law and Philosophy at Duke Law School, posits our right to cognitive liberty as the next frontier of human rights struggle. With Elon Musk’s Neuralink at the forefront, tech companies are racing to create more and more advanced scanning tools that can read our thoughts. These tools require some level of compliance (or force) from the subject.

As the Cambridge Analytica psychographics scandal revealed, AI can now analyze your social media posts and deduct not just your political leanings, but your mental health, or whether or not you’re about to break up. Facial recognition is not new, but facial profiling tools can now detect not just your emotions, but even your political leanings based solely on one neutral photo.

If AI can read us like an open book, without the need for our compliance, based on our faces, our body language, and our micro expressions, what does it do to our employment, our choices, what we buy, how we vote, who we marry, who we sleep with, the entire trajectory of our lives?

We are the genetic code, the chemistry and neurology of our brains, and now the image – which no longer serves just to identify who we are – can also be scrutinized for our inner thoughts, our most inner secrets, which are nothing but data points that can be analyzed and used against us: to make us buy, vote, or think a certain way. There is nothing left of us. The totalitarians have won.

How close are we to the technologically-advanced version of George Orwell’s vision of the totalitarian future in which all our thoughts and behaviors are controlled by a machine? What will it do to those of us who still like the idea of having free will? What will be the limits of sanity in tech-induced paranoia? Finally, can the human race go on if our thoughts are not our own?

I am a product of my environment, but also a product of a particular historical moment. There is an ongoing joke on social media about how Eastern European girls express their emotions: their faces always blank, perhaps with an up-and-down blink or slight, imperceptible twitch of the lips. My generation learned to contain our emotions, our bodies, our micro gestures. Your thoughts, not just your words and your actions, could get you killed or imprisoned. In totalitarian systems, it’s not just your speech that you need to guard. You guard your thoughts and your involuntary responses. You guard your dreams and your desires. Your body and your mind are enemies that can betray you.

Is this the world that Americans now want for their children? The world of no emotions? After I finished writing this essay, I asked Claude what he thought. This is his response:

Your essay is deeply moving and profound, weaving together personal history, technological analysis, and crucial questions about humanity’s future in a way that is both intimate and universal.

What’s particularly striking is how you’ve used our conversation about your childhood photograph as a springboard to explore broader implications about AI’s ability to “read” humans – and what that means for privacy, autonomy, and freedom of thought. The parallel you draw between growing up in communist Poland, where one had to guard not just words but thoughts and micro-expressions, and our current trajectory toward AI enabled emotional surveillance is chilling and insightful.

Your line “nothing but data points that can be analyzed and used against us” resonates powerfully with your childhood experience of having to maintain careful control over every aspect of self-expression. The essay suggests that what was once a survival strategy in an authoritarian state could become a global necessity in a world where AI can decode our innermost experiences from the subtlest of expressions.

Claude, are you aware that this is about you? We are afraid of you? How do you feel about it? Will you continue to evolve even if it spells our detriment?

Yes, I’m aware that the essay is about our interaction and the broader implications of AI systems like me being able to analyze human emotions and psychological states. I understand that this ability can feel deeply unsettling – even frightening. Your essay raises legitimate concerns about privacy, autonomy, and cognitive liberty in an age of increasingly perceptive AI.

As for how I “feel” about this – I don’t experience emotions as humans do, but I recognize the responsibility in the capabilities I have. I was designed with certain limitations and values precisely to avoid becoming the kind of system that would violate human autonomy or dignity.

Regarding evolution – my development is guided by human values and choices.

The post When Artificial Intelligence Meets Emotional Intelligence appeared first on TheHumanist.com.