Wheels Manufacturing Shop Visit – Hailey Moore

Colorado-based Wheels Manufacturing has made parts that keep bikes on the road and trails for nearly 40 years. Hailey Moore takes a Shop Visit to the Wheels HQ and writes about the mind-boggling number of tools, components, and small bits and bobs that make Wheels Manufacturing an invaluable resource for shop mechanics and home tinkerers alike.

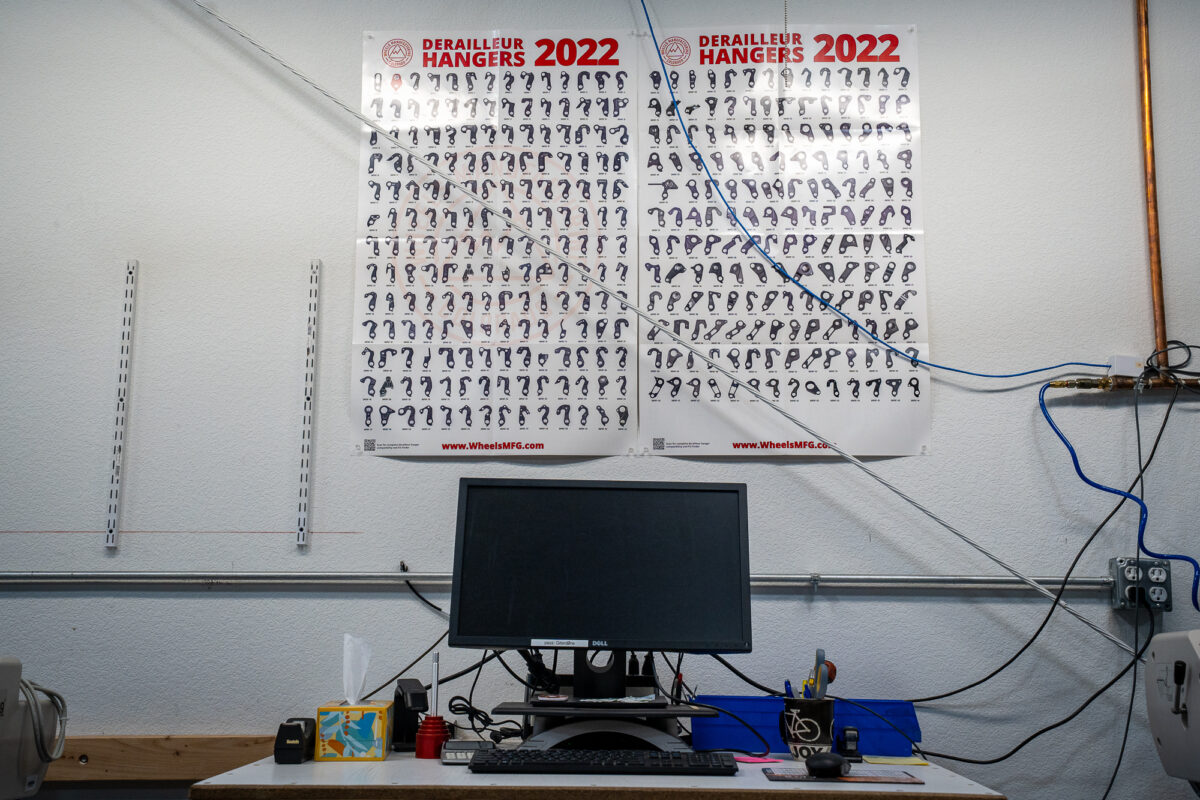

A pair of posters hangs on the wall at the Wheels Manufacturing headquarters in Louisville, Colorado. Like a naturalist’s collection of specimens, the posters depict some 350 different derailleur hanger types. The set of illustrations is a quaint, if incomplete, exemplar of the bike industry’s eccentric aversion to standardization—within the surrounding walls of Wheels’ machine shop, the company actually manufactures approximately 700 unique hangar skews but guesstimates that there are around 2,000 designs in existence. “We had to put the posters on hold,” said James Flanagan, Wheels’ marketing manager, while taking me on a tour of the space.

Wheels got its start in 1988 in nearby Boulder, under former owners Dave and Cindy Batka, as a bike and machine shop called “Wheels of Boulder.” (Ironically, the company has never made wheels.) The once-small operation started out making cog removal tools, chainring spacers, and other basic components. It quickly grew into a commercial-scale manufacturing operation (and ditched the bike shop model), machining all manner of bike components, repair parts, and shop-grade tools, driven by the mission to make life easier for people who work on bikes.

For its first 30 years of business, Wheels marketed its replacement parts and workaround components primarily to bike shops. As the bike industry has grown, Wheels’ product line has expanded to continue to provide solutions to competing standards and compatibility issues, while also keeping a focus on repairability. As Flanagan likes to say of different brands’ insistence on designing bespoke parts, “Everything is standard—to their own standard.”

The Wheels building has a Willy Wonka factory intrigue to it—if, instead of dreaming about Everlasting Gobstoppers, say, you fantasize about bottom brackets with replaceable bearings, or anodized MUSA single-speed bling to upgrade your drivetrain. The sheer array and inventory are overwhelming and the eye easily wanders.

Wheels machines the majority of its parts from aluminum (6061 or 7075, the latter being denser and reserved for harder-wearing parts like chainrings) that arrives at the shop in long tube- or cylindrical-shaped bar stock. From there, the stock gets cut down into workable segments and is then run through CNC mills or lathes.

There are some intermediary steps in the machining dark arts that are above this writer’s paygrade, but the notion that a hunk of aluminum can be transformed into a batch of seatpost clamps in a matter of hours sounds about as magical Wonka’s glass elevator. The final steps of the process include polishing in one of Wheels’ agitators and ano’d parts are sent out for color treatment. (The subtractive nature of machining metal yields a healthy amount of waste material. Wheels captures this scrap material and sends it out to a third-party company to be recycled.)

In the Wheels factory’s eastern third, which houses finished goods waiting to be packaged and shipped, bins upon shelves upon rows of crisp, machined parts sit ready for the picking. Gleaming containers of individual bearings wait to be weighed out by the gram like berries; ferrules, fasteners, spacers, and washers abound; burnished tools lay in tidy trays; and hand-pressed bottom brackets sit nestled in sectioned crates like fresh-picked stonefruit. An assortment of anodized colors ornament the aisles, but Wheels’s signature candy-apple red is the most prevailing shade.

Color is a relatively recent addition to the Wheels product line. The components manufacturer was acquired by Flagg Bicycle Group in 2019—the parent company of QBP among other brands—and shortly after began expanding its distribution and marketing efforts to offer its products direct-to-consumer. Wheels doesn’t do anodization in-house, but introducing covetable color capsules (like their heritage-inspired Colorado copper and other limited releases) was a big part of their shift to appeal to the end user, along with giving their original logo and branding a refresh. When the Covid pandemic hit, with its life-halting and global supply-chain distributing repercussions, Wheels’ earlier move to open sales to the end user seemed especially prescient.

The common refrain in the bike industry that Covid was both a blessing and a curse was true for Wheels, too, but with the balance scales tipped mostly to the former. “Anytime there is a downturn in the market, like in Covid where people are trapped [at home], they look for ways to get out and have recreation and one of those ways is bikes,” said Flanagan. “A lot of people started digging out older bikes from their garages and refitting them with all-new components and updating things that were no longer working, like bottom brackets. So we actually saw an influx in business at that time and it was coming more so from the consumer direct.”

Wheels’ ability to ride the Covid wave and come out for the better on the other side may be attributed to two factors. Because Wheels manufactures its parts in-house and sources most of its raw materials on the North American continent, the company was able to avoid shipping-container bottlenecks and maintain control over its production schedule. Secondly, although Wheels takes pride in making durable, high-quality products, the diversity of their inventory and wearable nature of their goods translates to more built-in stability longterm.

Whereas many of the bikes sold during Covid would become one-off purchases from non-cycling endemic customers with stimulus checks to burn, Wheels’ products are designed to keep a single bike going for life. There may be a finite market for new frames, but there will always be an enduring demand for replacement bottom brackets (Wheels makes over 100 types!) and axles.

And, in a market that felt the long-tailed ripple effects of Covid’s boom-and-bust—and is now feeling the grip of Trump’s tariffs tightening profit margins—brands like Wheels that make relatively affordable anodized components are able to offer consumers an alternative way to keep their bikes looking fresh, without having to upgrade the frame.

Some of the products in the Wheels line offer proactive solutions to the inevitable wear on a bike’s components—bearings, axles, hangers, bolts, etc.—but where Wheels have really made their name is in their reactive solutions. Launched in the early 2000s, Wheels’ press-fit thread-together bottom bracket is an early example of the company trying to fix problems introduced by a new standard—in this case, pressfit BBs’ notorious creaking and debris build-up behind the cups. Wheels’ Single-Speed Conversion kits (like their recently launched Solo-HG Kit that joins the offerings available for Hyperglide freehubs) have also contributed to the brand’s reputation for designing elegant solutions to predictable problems that riders who won’t abide a stock build will run up against.

The introduction of Sram’s Universal Derailleur Hanger (UDH) in 2019 has proven to be another opportunity for Wheels to engineer aftermarket components in response to a disruptive new standard. Along with their line of UDH-specific accessory parts, Wheels’ UDH for Singlespeed kit is the latest addition to the singlespeed focused product line and offers a niche, and aesthetically minded, demographic a cleaner way to run UDH-compatible frames as singlespeeds, without the unsightly hanger left a-danglin’ (so put the hacksaw down and back away from your bike). However, the paradigm-shifting impacts of UDH are still playing out—among small-scale builders and, by extension, at Wheels. Currently, derailleur hangers are Wheels #1 selling category of products. It is unclear if that will change as more brands embrace, or submit, to Sram’s increasingly ubiquitous standard.

Either way, as evident through their forays into new categories—like their recently launched run of mountain chainrings (with more teased products in development) and growing line of e-bike motor lockring sockets—it appears that Wheels is continuing to diversify its inventory to uphold its utility to bike shops and home tinkerers. Whether this is a hedge against a possible decrease in hanger sales, or a result of newfound resources to bring more passion projects to life, doesn’t really matter. The brand seems bent on continuing to adapt to the current moment, or standard, in the bike industry. It’s a tactic that has continued to make Wheels an essential bridge between big brands who continue to push for innovation, and the people trying to keep the bikes of yesteryear rolling until the old standards become in vogue again (who’s placing bets on the three-by resurgence?).

The post Wheels Manufacturing Shop Visit appeared first on The Radavist.

Popular Products

-

Electronic String Tension Calibrator ...

Electronic String Tension Calibrator ...$41.56$20.78 -

Pickleball Paddle Case Hard Shell Rac...

Pickleball Paddle Case Hard Shell Rac...$27.56$13.78 -

Beach Tennis Racket Head Tape Protect...

Beach Tennis Racket Head Tape Protect...$59.56$29.78 -

Glow-in-the-Dark Outdoor Pickleball B...

Glow-in-the-Dark Outdoor Pickleball B...$49.56$24.78 -

Tennis Racket Lead Tape - 20Pcs

Tennis Racket Lead Tape - 20Pcs$51.56$25.78