Chartbook 378: The Anxiety Of Influence: Economic Geography, Canada And The Usa.

Eyes around the world are on Canada and the election to be held tomorrow, Monday 28th April. Cam Abadi and I took on the topic for the Ones and Tooze podcast this week.

As so often, the conversation with Cam drove me to research something “big” and important and obvious that I had not previously thought about. In this case, Canada and the economic geography of North America.

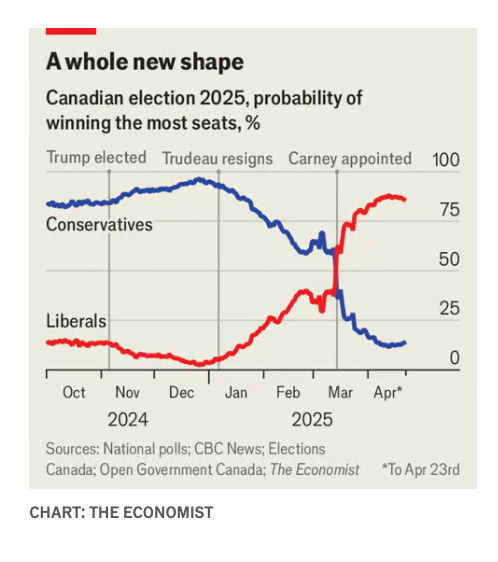

Trump’s super aggressive trade policy has upended the Canadian election.

Since roughly 20 percent of Canadian GDP is accounted for by exports to the US, one can see why trade policy matters. Carney has been boosted into the lead as a safe pair of hands and a liberal Canadian patriot.

Cam, however, had come across the fascinating fact that it was not just trade policy with the USA that was at stake. In the Canadian elections, intra-provincial trade was an issue. We both wondered why.

As it turned out, it goes to the fundamental properties of Canada as a state.

Canada is a federation, one of the most decentralized in the world. So much so that Canada’s constitution does not explicitly guarantee free trade between provinces. In 2017 Canada signed a Free Trade Agreement

with itself!

When you get to the economic data the upshot is even more surprising. According to statistics from RBC, the volume of Canadian trade with the US is larger than the combined volume of intra-provincial trade within Canada.

Source: RBC

By this measure, the provinces that make up Canada as a federation are more integrated on the North-South axis with their Southern neighbor, the United States, than they are on the East-West axis between each other. Important context, when you consider the challenge to Canadian sovereignty posed by Donald Trump.

If this economic geography blows your mind - I will admit I was a bit flabbergasted - take a look at a map of Canadian population density and you can see why this might be the case.

Canada population density (2014) Source: Wikipedia

Canada’s population of 40 million is basically strung out in a series of patches of urban concentration along the Southern border that stretch from Vancouver in the West to St John’s in the East, with 50 percent of the population in the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor.

One commonly quoted statistics (I can’t vouch for it, but it does not seem entirely implausible), is that 90 percent of Canada’s population lives within 150 miles of the Southern border.

A while back, Vox zoomed in on this bizarre geographic fact:

The densely populated parts of Canada are all close to the United States. Some of them produce oil sold to the USA, or are part of the motor vehicle supply chain, which is deeply connected to the USA. At the same time those regions of Canada are separated from each other by huge distances. So, extremely high intensity trade between the oil producers of Alberta or the car factories of Windsor and their US counterparts, overshadows the thinner trade connections between the main areas of Canadian settlement.

In terms of capital investment the figure are striking:

The United States is Canada's largest investor, with U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI) in Canada totaling $438 billion as of 2022. Canada, in turn, is a significant investor in the U.S., with a stock of FDI of $683 billion.

But it is not just economics and geography that are in play. Intra-Canadian politics maintains a network of trade barriers and regulations that impede trade within Canada itself.

As RBC comments

While some trade barriers, like the physical distance between two provinces, are obvious and unchangeable, other non-geographic internal barriers are more complex and less visible. These arise from differences in how provinces recognize rules, regulations and standards. For example, occupational health and safety or environmental standards may vary between provinces, creating compliance challenges and additional costs for businesses seeking to expand into other provinces. Canada’s constitution does not explicitly guarantee free trade between provinces, and its decentralized federal system grants provinces significant authority to regulate and oversee trade within its borders. Many trade barriers are imposed to protect local industries, uphold regulatory standards, generate revenue, and preserve jurisdictional autonomy. However, prioritizing narrow economic interests over fostering broader standards across the country has hindered achieving economies of scale, reduced competition, and contained productivity growth in Canada—trends that will continue unless meaningful action is taken.

You don’t have to dig very deep in Canadian political economy to find intense arguments over the relative priority of business interests, politics, technology and geographical factors in shaping the degree of economic integration or lack of it.

The stakes are high, or at least educated opinion claims they are. $200 billion Canadian could be in play.

Others disagree. They liken the promise of huge gains to be made by sweeping away long-standing, deeply entrenched barriers to the fantastical imaginings of 19th-century European explorers and map-makers when it came to Canada’s interior riches.

Charles Napier Sturt — I want you to remember this name. Sturt was a British army officer who contributed much to the mapping of the Australian interior. He and other members of an official 1844 expedition risked their lives trying to find a freshwater inland sea deep in Australia’s desert regions. So sure was Sturt of the sea’s existence that the expedition included a boat and some sailors to pilot it (!). The idea, of course, turned out to be an illusion.

Their priority is to see Canada investing in updating its economic model and breaking the heavy dependence on the real estate bubble that has inflated Canadian balance sheets and household debt, but has not delivered much productivity growth in recent years.

A long history of inter provincial inefficiencies cannot easily explain Canada’s retarded productivity growth compared to other OECD countries.

Or is divergence from the United States over the last ten years.

So there are big economic issues to address here.

But step back one more time from immediate debates of economic policy. Focus again on the simple measure of population density and ask yourself, what would we see if we panned back to view all of North America, placing Canada’s thinly-spread population alongside that of the United States and Mexico? It is this map which gives one a sense of why, beyond Trump’s nonsense, an anxiety and urgency suffuses the US-Canada conversation.

Remove the boundary demarcations and the national labels from this map and you would “see” a sprawling mass of population inland from the East Coast that you might label “the USA”. You would see another massive concentration further to the South that you might label “Mexico”. But you would be hard-pressed to identify a separate entity to call “Canada”.

This weekend, even AI seems to be conspiring to make the point. If you google the innocent search term “Canada population”, the engine gives you this graph:

A comparison of Canada not with other sovereign states, but with California and Texas.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to 150,000 readers around the world. What supports this writing are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to join the supporters’ club.