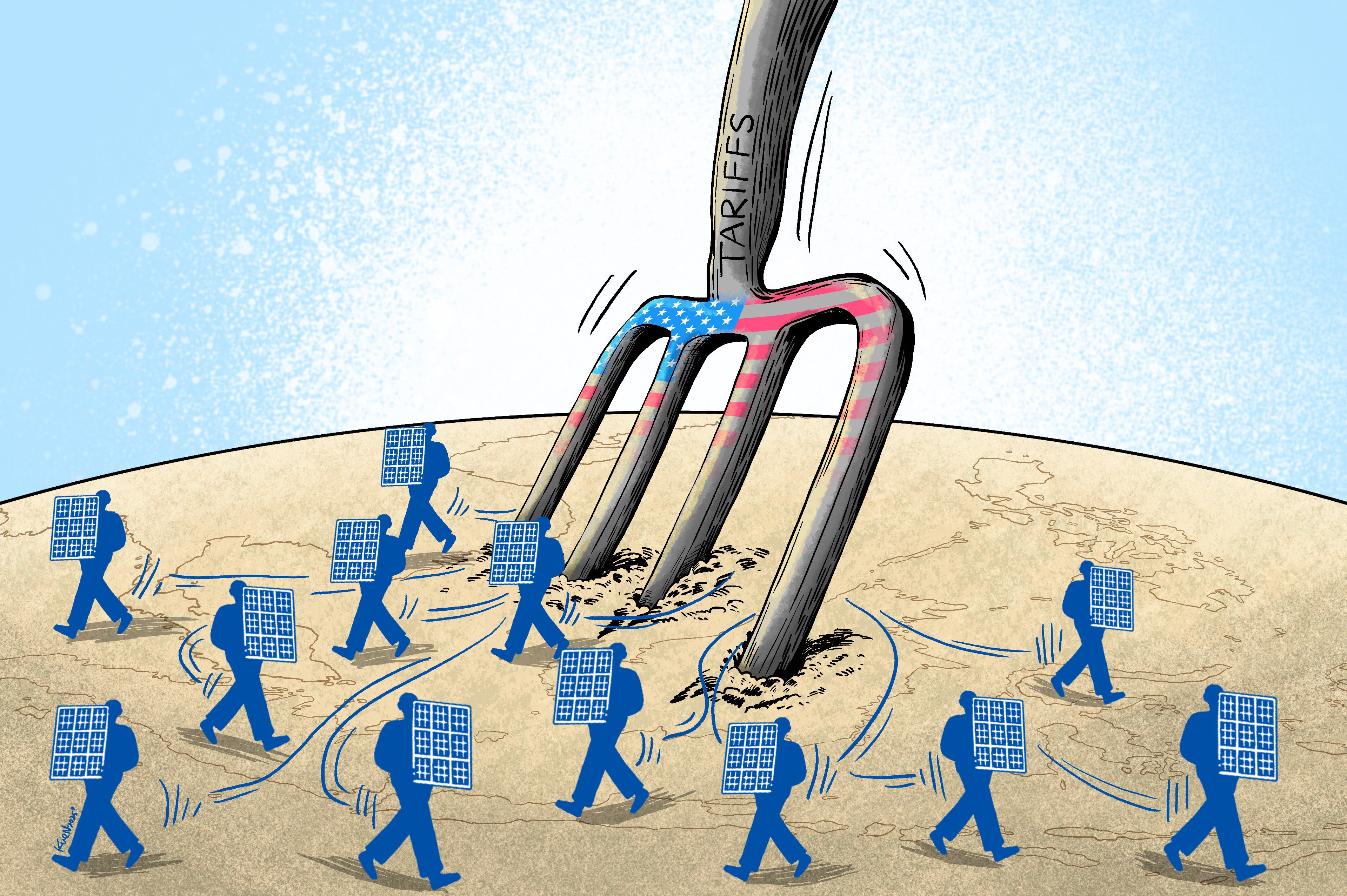

Can Chinese Solar Cell Producers Dodge Trump’s Looming 3,521% Import Tariffs?

After a cat-and-mouse tariff game over the past 13 years, the rivalry between the US and China in the global solar panel industry is heading into crunch time.

The latest threat by US President Donald Trump to impose a fresh round of heavy duties on solar cells and modules shipped from four Southeast Asia nations – allegedly produced with “transnational subsidies” from Beijing – could land a major blow to the trade dominated by Chinese companies.

The tariffs of up to 3,521 per cent if confirmed by June would “virtually block” US solar cell imports from Chinese-owned factories in Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand, according to Citigroup. With higher costs, the duties would erode Chinese firms’ competitiveness in the lucrative US market, Huatai Securities said.

“Obviously, this Trump shock has made a lot of governments and companies rethink their strategies,” said Grant Hauber, strategic energy finance adviser for Asia at the Ohio, US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “If I was a solar manufacturer, I would not be expanding my plants any more. Put that on hold. Use the capacities you have and reprogramme the end markets.”

The US Department of Commerce announced on April 21 wide-ranging anti-dumping and subsidies tariffs on about US$12 billion of solar-cell exports from the four Southeast Asian countries, hitting some companies in Cambodia with duties as high as 3,521 per cent. Trina Solar’s Thailand unit was slapped with combined tariffs of 375 per cent, while JA Solar’s Vietnam unit was charged 120.6 per cent.

The measure was the biggest yet of several rounds of trade actions against solar materials from Asia, following complaints from US-based units owned by South Korea’s Hanwha Qcells and Arizona-based First Solar that Chinese factories were flooding the market with “unfairly cheap” shipments.

Before the latest blow, most solar cells – including those already assembled into panels – imported into the US from these four nations were already liable to separate sector-specific duties imposed by the Biden administration. They comprised preliminary anti-dumping duties of 17.8 per cent to 271.3 per cent announced in late November and preliminary anti-subsidies duties of 2.9 per cent to 293 per cent in early October.

Under Trump’s Make America Great and manufacturing reshoring campaign, the US imposed a 10 per cent baseline tariff on nearly all imports, reigniting a trade war. In addition, Trump also slapped on various levels of “reciprocal tariffs” to help trim the US trade deficit, with duties on some Chinese goods skyrocketing to as high as 245 per cent.

The tariffs originally announced for the biggest exporters of solar panels to the US were 24 per cent for Malaysia, 36 per cent for Thailand, 46 per cent for Vietnam and 49 per cent for Cambodia.

“Certain companies have relocated their solar cell supply chain to third countries, such as Indonesia and Laos, to avoid the anti-dumping and countervailing tariffs, at the cost of higher unit production cost,” Pierre Lau, head of Asian utilities and clean-energy research at Citigroup, said in a report on Wednesday.

Chinese manufacturers, which control over three-quarters of global supply, were likely to abandon their export model and use only their factories in the US to satisfy demand in the country, analysts said. As such, tougher trade barriers would do little to chip away at their dominance.

“The Chinese players should prevail over US domestic players as their technology and cost control capabilities are better,” said Dennis Ip, regional head of utilities and renewables research at Daiwa Capital Markets “The US is still the most important market, as the markets in Europe and China are not profitable.”

What makes the US market attractive is not its size – 50 gigawatts (GW) or roughly 10 per cent of global annual installation – but the profit margins, said Frank Haugwitz, founder of consulting firm Asia Europe Clean Energy (Solar) Advisory.

With subsidies supporting the huge price premium of US solar panels – at US$0.26 per watt compared with 0.75 yuan (US$0.10) per watt in mainland China, the US solar supply chain can absorb the current tariffs charged on panel and component imports, Cai Zihao, an analyst at Minmetals Securities, said in a report on April 16, citing data published by Infolink Consulting.

Chinese solar producers’ efforts to avoid US penalties have been going on for more than a decade. They have built factories in Southeast Asia and shipped their goods to the US from there, skirting steep tariffs imposed on direct imports from mainland China.

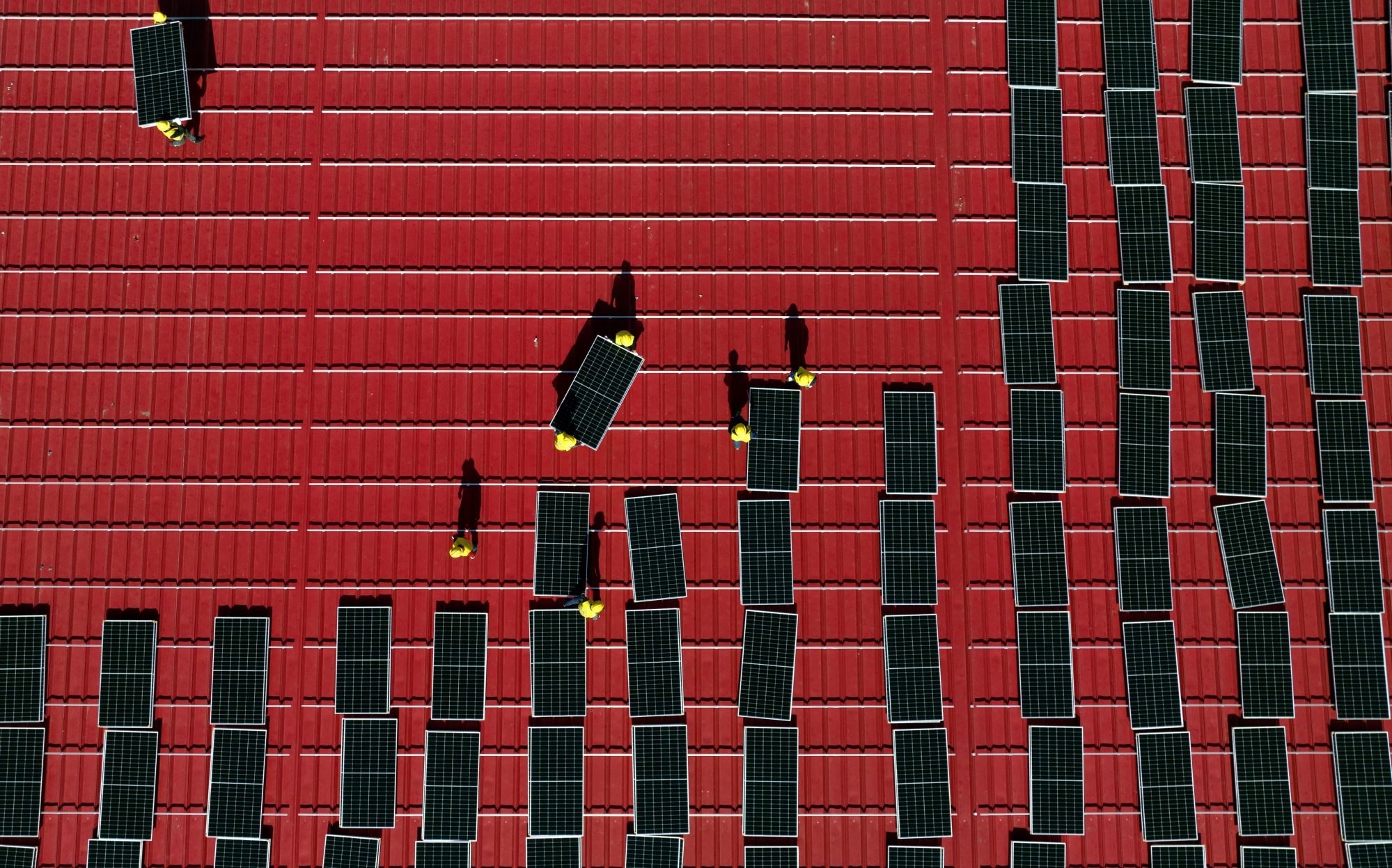

Many of the biggest Chinese solar sector players – including Longi Green Energy Technology, JinkoSolar, Canadian Solar, Trina Solar and JA Solar Technology – had also built solar-panel assembling capacities of 2 to 5GW each in the US to prepare for the day when the export-model “loophole” was shut, Ip said.

However, they were unlikely to commit to spending on new US capacity in the short term as the tariff war escalates, he said. It’s also unclear whether Trump – a climate-change sceptic and fossil-fuel supporter – would dismantle clean energy subsidies passed in 2022 during the Biden administration, he added.

Trump suspended renewable energy tax credit disbursements related to the Inflation Reduction Act in an executive order on his inauguration day in January, potentially affecting the investment returns of many solar projects in various stages of development.

Most of the US cell imports would probably shift from Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia to India and the Middle East, analysts said. Turkey and Saudi Arabia were also among target markets for Chinese manufacturers to establish plants to serve both the US and other regional markets, said Jessica Jin, principal analyst, clean energy technology at S&P Global Ratings.

Some of the transfer has already been reflected in trade flows after the preliminary duties were announced late last year.

Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia and Malaysia’s combined share of the US solar cells market by value plunged to 38 per cent in the first two months this year, from 79 per cent in 2024, according to data published by the US International Trade Commission. The tariffs, on top of lower product prices, have reduced US solar cell imports by 74 per cent to US$620 million from a year earlier.

On a global basis, China held 75 to 97 per cent of the market in four stages of the solar supply chain as of 2021 – spanning polysilicon, wafers, cells and panels – according to data from the International Energy Agency.

Given China’s dominance and agility across the global supply chain, fresh US tariffs would do little to break America’s reliance on foreign solar materials and components, according to Coalition for a Prosperous America.

Chinese-owned solar panel facilities accounted for 39 per cent of total capacity in the US, compared with 24 per cent by US-owned entities and 37 per cent from other origins, the group estimated.

“The [past] tariffs had little effect on the volume of imports, which continued to rise for the last 12 years [as] importers have found one loophole after another,” through rounds of relocation of capacity from tariff-hit nations to less affected ones, it said.

The coalition attributed past tariffs’ ineffectiveness to narrowly drawn US tariff laws that required findings of specific violations like “dumping” – selling below-cost in the home country, and Chinese firms’ ability to shift production rapidly.

For example, capacity was being built in Indonesia, Laos and the Middle East in recent years, it noted. Figures from the US International Trade Commission indicated some of these new export destinations were already booming.

Indonesia’s share of solar cell imports into the US jumped to 19.5 per cent in this year’s first two months from 2.1 per cent in the same period last year, while that of Laos rose to 18.1 per cent from 0.1 per cent.

Chinese “overproduction” of solar panels and components has put the US manufacturing industry “in crisis”, the coalition said. Few independent US-owned producers would remain in business long-term, the non-profit said in a report in January.

“The US is at risk of losing its entire solar [panel] manufacturing industry, despite 13 years of tariffs, two years of federal tax credits and billions of dollars of private investment,” it said in a report.

It is difficult for home-grown companies to build polysilicon, wafer and cell capacity in the US due to a lack of domestic experienced workers and expertise, Haugwitz said. High US labour costs were also a challenge, he added.

“Solar-panel manufacturing is relatively simple, but if you also want to make solar cells in the US, the expertise required and the costs will be higher,” S&P’s Jin said. “Without subsidies, this is certainly not viable.”

Volatile US policy – including on subsidies – was another barrier, according to Hauber at Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Not many US companies would invest in America under “these too unstable and too unpredictable conditions”, he said

This could threaten the sector’s financial health, said David Fishman, senior manager at energy consultancy The Lantau Group.

Chinese solar supply chain players, most of which were already mired in substantial losses last year due to oversupply, would likely suffer from a decline in demand this year in their home market, he noted. This could pressure their profitability and cash flow further, he added.

A possible way for them to continue their overseas expansion while reducing the cash outlay would be to relocate their factory equipment instead of procuring new hardware, Cai at Minmetals Securities said. This could help improve capacity utilisation and hence profitability, he added.

“There is a lot of political risk right now,” Fishman said. “But if the US is cracking down on [imports], and [saying] that you have to come to the US to set up a factory, I think some will be willing to do it. If that is the only way to earn money, they will try to do it.”